Program Notes—Gaelic

Program Notes

GAELIC

March 9 | 4:00 PM—Lensic

The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra

Guillermo Figueroa, Music Director

The Santa Fe Youth Symphony

William Waag, Conductor

Sirena Huang, Violin

JEAN SIBELIUS

Finlandia, op.26

Born 1865, Tavastehus, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

Finlandia has become a symbol of Finland and its national aspirations, but this music achieved that status only indirectly. Finland was under Russian control throughout the 19th century. Sibelius had grown up speaking Swedish, but as a young man he became a committed Finnish nationalist. In February 1899, Czar Nicholas II of Russia issued his “February Manifesto,” launching an intense Russification campaign and severely limiting freedom of the press in Finland. The reaction against this decree was swift, and in June 1899, events were held in Helsinki to advocate for a free press and raise money for newspaper pension funds. For that occasion, Sibelius wrote a short piece for orchestra that he titled Finland Awake! So obvious was the meaning of that title that Russian authorities banned its performance, and Sibelius retitled the piece Finlandia when he revised it the following year. This fiery music quickly caught the heart of the Finnish people and became a symbol of their national pride. The Finns would finally gain their independence from Russia after World War I, but Finlandia has remained a sort of unofficial national hymn ever since.

Yet this music tells no story, nor does it incorporate any Finnish folk material. Many assumed that music that sounds so “Finnish” must be based on native tunes, but Sibelius was adamant that all of it was original: “There is a mistaken impression among the press abroad that my themes are often folk melodies,” he wrote. “So far, I have never used a theme that was not of my own invention. The thematic material of Finlandia . . . is entirely my own.”

Finlandia is extremely dramatic music, well-suited to the striving and heroic mood of the times. Its ominous introduction opens with snarling two-note figures in the brass, and they are answered by quiet chorale-like material from woodwinds and strings. At the Allegro moderato the music rips ahead on stuttering brass figures and drives to a climax. Sibelius relaxes tensions with a poised hymn for woodwind choir that is repeated by the strings (surely this was the spot most observers identified as “authentic” Finnish material). The music takes on some of its earlier power, the stuttering brass attacks return, and Sibelius drives matters to a thunderous close.

Small wonder that music so dramatic and composed at so important a moment in Finnish history, should have come to symbolize that nation’s pride and desire for independence.

— Program note by Eric Bromberger

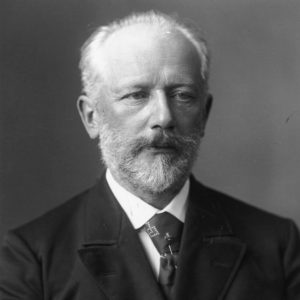

PYTOR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Violin Concerto in D Major, op.35

Allegro moderato

Canzonetta

Allegro vivacissimo

Born 1840, Votkinsk

Died 1893, St. Petersburg

Tchaikovsky wrote his Violin Concerto in Switzerland during the spring of 1878, sketching it in 11 days and then completing the scoring in two weeks. Without asking permission, he dedicated it to the famous Russian violinist Leopold Auer, who was concertmaster of the Imperial Orchestra and who would later teach Heifetz, Elman, Zimbalist, and Milstein. Tchaikovsky promptly ran into an unpleasant surprise: Auer refused to perform the concerto, expressing doubts about some aspects of the music and reportedly calling it “unplayable.” The concerto had to wait three years before Adolph Brodsky gave the premiere in Vienna on December 4, 1881.

The premiere was the occasion of one of the most infamous reviews in the history of music. Eduard Hanslick savaged the concerto, saying that it “brings to us for the first time the horrid idea that there may be music that stinks to the ear.” He went on: “The violin is no longer played. It is yanked about. It is torn asunder. It is beaten black and blue . . . The Adagio, with its tender national melody, almost conciliates, and almost wins us. But it breaks off abruptly to make way for a Finale that puts us in the midst of the brutal and wretched jollity of a Russian kermess. We see wild and vulgar faces, we hear curses, we smell bad brandy.”

Hanslick’s review has become one of the best examples of critical Wretched Excess: the insensitive destruction of a work that would go on to become one of the best-loved concertos in the repertory. But for all his blindness, Hanslick did recognize one important feature of this music: its essential “Russian-ness.” Tchaikovsky freely and proudly admitted his inspiration for the work: “My melodies and harmonies of folk-song character come from the fact that I grew up in the country, and in my earliest childhood was impressed by the indescribable beauty of the characteristic features of Russian folk music; also from this, that I love passionately the Russian character in all its expression; in short, I am a Russian in the fullest meaning of the word.”

The orchestra’s introduction makes for a gracious opening to the concerto, for the solo violin quickly enters with a flourish and then settles into the lyric opening theme, which had been prefigured in the orchestra’s introduction. A second theme is equally melodic—Tchaikovsky marks it con molt’espressione—but the development of these themes places extraordinary demands on the soloist, who must solve complicated problems with string-crossing, multiple-stops, and harmonics. Auer was wrong: This concerto is not unplayable, but it is extremely difficult (and Auer later admitted his error and performed the concerto). Tchaikovsky himself wrote the brilliant cadenza, which makes a gentle return to the movement’s opening theme; a full recapitulation leads to the dramatic close.

Tchaikovsky marks the second movement Canzonetta (“Little Song”) and mutes solo violin and orchestral strings throughout this movement, which feels like an interlude from one of his ballets. It leads without pause to the explosive opening of the finale, marked Allegro vivacissimo, a rondo built on two themes of distinctly Russian heritage. These are the themes that reminded Hanslick of a drunken Russian brawl, but to more sympathetic ears they evoke a fiery, exciting Russian spirit. Once again, the solo violin is given music of extraordinary difficulty. The very ending, with the violin soaring brilliantly above the hurtling orchestra, is one of the most exciting moments in this—or in any—violin concerto.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

AMY BEACH

Symphony in E minor, op.32 “Gaelic”

Allegro con fuoco

Siciliana, Allegro vivace

Lento con molto espressione

Allegro di molto

Born 1867, Henniker, NH

Died 1944, New York City

“Gaelic” is the work of a 29-year-old American woman who had no training in composition. That by itself would make it unique; the fact that it is the best American symphony from the end of the 19th century makes it an extraordinary achievement.

A child prodigy, Amy Marcy Cheney appeared as piano soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at 17 and also began composing. At age 18, she married the Boston surgeon H.H.A. Beach, who, although a cultivated man musically, did not want his wife performing in public. He did, however, encourage her to compose. Beach had no formal training as a composer (which in her day meant European training), and she was essentially self-taught. Nevertheless, over the next several decades she produced a sequence of successful large-scale works, and her Mass in E-flat (1890) was the first work by a female composer presented by Boston’s Haydn and Handel Society. Upon the death of her husband in 1910, Beach, then 43, resumed her career as a concert pianist, making a particularly successful series of tours through Europe. She composed prolifically throughout her life: Although her list of opus numbers runs to 152, she actually wrote about 300 works. She was still active as a pianist and composer at the time of her death in 1944 at 77.

Beach began work on her Symphony in E Minor in November 1894 and completed it in 1896; conductor Emil Paur led the Boston Symphony Orchestra in its successful premiere on October 30, 1896. This symphony is very much a product of its time. When Beach began it, Antonín Dvořák was still teaching at the National Conservatory of Music in New York, and his influence on American composers was enormous. Although works like his “New World” Symphony and “American” Quartet were written and premiered while Beach was working on this symphony, Dvořák insisted that these remained “his” music (Bohemian music), and he suggested that young American composers turn to native materials and make a national music out of them.

Dvořák specifically recommended Native American and African-American music as possible sources, but Beach—who heard the Boston premiere of the “New World” Symphony—did not regard either of those as part of her musical heritage. Instead, she noted: “We of the North should be far more likely to be influenced by the old English, Scotch or Irish songs, inherited with our literature from our ancestors.” For her symphony, she turned to the folk music of Ireland (thus the nickname “Gaelic”) and used four themes of what she called “simple, rugged and unpretentious beauty.”

The Symphony in E Minor is a big work: Its four movements stretch out to 40 minutes. Beach may have based the symphony on Irish melodies, but for the first movement she draws on quite a different source: her own music. This Allegro con fuoco employs two themes from Beach’s 1892 song “Dark is the Night,” which is set to a text by William Ernest Henley. Some sense of the character of that song (and of the symphony’s opening movement) may be felt in its final lines:

A wild wind shakes the wilder sea . . . O, dark and loud’s the night.

This sonata-form movement is based largely on its turbulent opening idea, full of brass calls and a more flowing second subject introduced by the violins. The movement builds to a grand climax and drives to a forceful conclusion on a unison E from the entire orchestra.

The second movement consists of sections at two different tempos. In the gentle opening Siciliana in 12/8, solo oboe sings the old Irish song “The Little Field of Barley” before the music suddenly races ahead at the Allegro vivace, a particularly effective scherzo. The song melody returns, now in a graceful solo for English horn, and Beach rounds the movement off with a quick recall of its scherzo section.

Beach said that the Lento con molto espressione portrays “the laments of a primitive people, their romance and their dreams,” and she based it on two Irish folksongs, “Cushlamachree” and “Which way did she go?” This movement features extended solos for violin and cello, and its lovely concluding episode for strings extends these themes sensitively.

The Allegro di molto finale bursts to life with a dramatic beginning. Beach said that this movement depicts the “rough and primitive character of the Celtic people, their sturdy daily life, their passions and battles.” Like the first movement, the finale is in sonata form based on several themes, and these include a recall of material from the opening movement, which is woven into the development. The movement drives to a climax that Beach asks to be played con gran forza and a full-throated conclusion marked triple forte.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger