Program Notes | Beethoven’s Ninth

Sunday, May 19, 2024 / 4:00 PM

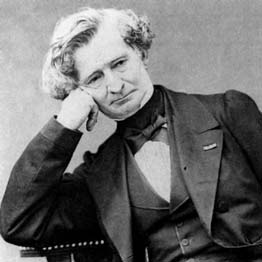

HECTOR BERLIOZ

Born 1803, Grenoble

Died 1869, Paris

Les Nuits de’ete

By the time Berlioz began composing Nuits d’été (Summer Nights), he had become embittered by his failure to establish himself as a composer and musical force in Paris. Over the previous decade, he had created a series of large-scale works that are today a central part of the repertory: Symphonie Fantastique, Harold in Italy, the Requiem, the opera Benvenuto Cellini, and Romeo and Juliet. But Parisian audiences and tastes remained hostile to the composer, and Berlioz had been forced to support himself as a music critic. Perhaps exhausted by this struggle, he turned away from large compositions, and in the summer of 1840 he began to compose songs on texts by the French novelist and poet Théophile Gautier.

Berlioz had met Gautier (1811-1872) when the two were both still very young men. He chose six poems from the poet’s La comédie de la mort (1838), and the songs were published in 1841. By the mid-1850s, he had orchestrated them all, in the process creating the first set of orchestral songs. However, Berlioz heard only two of the songs in their orchestral version.

The songs all touch upon some aspect of love, but Nuits d’été does not form a true song cycle; there is neither unity nor a progression across the span of the songs, and individual songs from the set are sometimes sung separately.

Berlioz was a master of the orchestra, and he used that rich palette of color to intensify the atmosphere and meaning of these songs. The set includes a villanelle, which is a rustic or rural song, and the springtime atmosphere of this opening song is underlined by its harmonic freshness. Le spectre de la rose, with its striking subject (the flower that celebrates the occasion of its own death), has become one of the best-known of the set; Berlioz expanded the introduction when he arranged it for orchestra. The next three songs are dark, and they all might take their cue from the subtitle of the first: Lamento. These pieces remind us that death, separation, and pain are all part of love. Absence was the first of these to be orchestrated; Berlioz made the arrangement in 1843 for his companion during these years, the soprano Maria Recio.

The atmosphere changes completely in the final song, L’ile inconnue. It is charged with romantic expectancy; the rocking rhythms mirror the motion of the boat as it sails toward a land of infinite possibility, and over the final pages the piano’s steady murmur of sixteenths echoes the sound of the wind that propels the poet toward an unknown fulfillment.

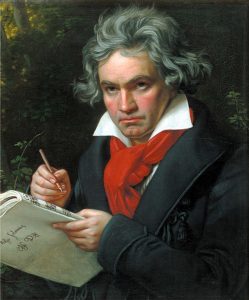

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born 1770, Bonn

Died 1827, Vienna

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, op.125

Beethoven’s Ninth is at once his grandest symphony and his most challenging, and its challenges have been both moral and musical. The unprecedented grandeur of Beethoven’s music, the first use of voices in a symphony, and in particular the setting of Schiller’s “An die Freude” have made the work one of the great statements of romantic faith in humankind, a utopian vision of the universal bond of all people.

The Ninth seems so perfectly conceived that it comes as a surprise to learn that it took shape very slowly over a span of 30 years, and Beethoven’s conception of the music changed often during that process. He first planned to compose a setting of Schiller’s “An die Freude” as early as 1792, when he was just 22 (Schiller had written that ode seven years earlier). Although he set that intention aside, the idea remained with him and was not mentioned again until 20 years later, when Beethoven noted such a plan in his sketchbooks. An invitation from the London Philharmonic in 1817 to write two symphonies finally prodded the composer to action (although the London visit never took place). The Ninth was completed in early 1823.

At this point in his career, Beethoven had formulated what we know as his “late style,” which includes an inward and lyrical expressiveness and a new interest in variation-form and contrapuntal writing. While the Ninth Symphony incorporates these features, Beethoven reverted partly to his heroic style, that powerful approach built on conflict and triumphant resolution that had animated such works as the Third, Fifth, and Seventh Symphonies.

The first performance of the Ninth took place in Vienna on May 7, 1824, when Beethoven was 53. He had been deaf for years, but he sat on stage with the orchestra and tried to assist in the direction of the music. This occasion produced one of the classic Beethoven anecdotes. Unaware that the piece had ended, Beethoven continued to beat time and had to be turned around to be shown the applause that he could not hear; the realization that the music they had just heard had been written by a deaf man overwhelmed the audience.

The opening of the Allegro ma non troppo, quiet and harmonically uncertain, creates a sense of mystery and vast space. The ending opens with ominous fanfares over quiet tremolo strings, and out of this darkness the main theme rises up one final time and is stamped out to close the movement. The second movement, marked Molto vivace, is a scherzo built on a five-part fugue. The displaced attacks in the first phrase, which delighted the audience at the premiere, still retain their capacity to surprise; Beethoven breaks the rush of the fugue with a rustic trio for woodwinds and a flowing countermelody for strings. The third movement, Adagio molto e cantabile, is in straightforward theme-and-variation form with contrasting interludes.

After the serenity of the third movement, the orchestra erupts with a dissonant blast for the famous finale. Schiller’s text exalts the fellowship of mankind and man’s recognition of his place in a universe presided over by a just and omnipotent god. Musically, the movement is a series of variations on the opening theme, the music of each stanza varied to fit its text.

In a world that daily belies the utopian message of the Ninth Symphony, it may seem strange that this music continues to work its hold on our imagination. It is difficult for us to take the symphony’s vision of brotherhood seriously when each morning’s headlines show us again the horrors of which man is capable. Perhaps the secret of its continuing appeal is that for the hour it takes us to hear the work, the music reminds us not of what we too often are, but of what, at our best, we might be.

—Program Notes by Eric Bromberger