Program Notes | Music of the Spheres

Tuesday, April 25—4:00 pm

ALEKSEY IGUDESMAN

ALEKSEY IGUDESMAN

Born 1973, Leningrad

On a Bus In Uruguay

Three guesses as to where I wrote “On a bus in Uruguay”. That’s right, on a flight to Japan!

In all seriousness, I love writing music while moving and during travel ,and I did indeed write this piece on a bus ride from Montevideo to Punta del Este. The accompaniment is a musical reflection of the motion of the bus. Although it is not particularly Latin in style, it still fits emotionally in my violin duet book “Latin & More”.

–Program Note by Aleksey Igudesman

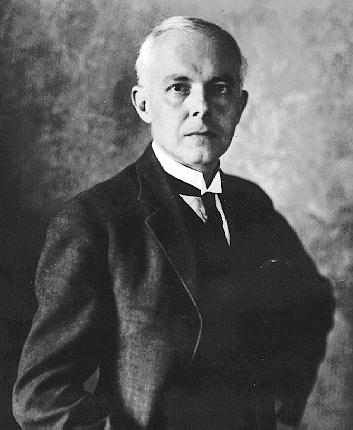

BÉLA BARTÓK

BÉLA BARTÓK

Born 1881, Hungary

Died 1945, New York City

Selections from 44 Duos for Two Violins, Sz 98, Bb 104

Like his close friend, the composer Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók was concerned with the musical education of children. He composed many piano pieces for children, mostly based on his extensive collection of folk music from Southeast Europe and the Middle East, and culminating in the monumental Mikrokosmos.

Béla Bartók, Jr., the composer’s son, wrote: “Although taking their ages into account, [Bartók] looked on children as full human beings. He sought to give them every possible help in improving their level of education. As far as music went, he tried to establish a basic musicianship in the malleable core of a child’s character, which would enable the child to develop into a more worthwhile member of the human race.”

In 1930, musicologist and music teacher Erich Doflein (1900-1977) asked Bartók for permission to adapt several of the composer’s piano pieces for two violins, as part of a series of graded study pieces for young violinists. Under the name of music-educational theory, Doflein and his wife developed a system of progressive musical education that combined contemporary music and older music suited for teaching purposes.

Bartók preferred to write new duos, creating 44 works of advancing difficulty that he published in four volumes in 1933. All but two are based on authentic folk themes, including Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, Ukrainian and Arabic melodies. His goal was to present to young players the beautiful simplicity of folk music. While written with pedagogical intent, the pieces transcend their teaching aims to stand by themselves as perfectly poised works. They comprise a wide variety of tempi and moods. Various groupings are frequently performed in concert.

–Program Note by Erick Bromberger

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS

Born 1964, New York

Silent Moon

Silent Moon is a reference to the break in the stillness of winter that is indicative of a gathering of energy. Like the silence before the storm, Silent Moon offers an opportunity to cleanse the past so that we might better shift our attentions to future growth.

This concept is often depicted through certain double-visaged gods and goddesses such as Janus, who looks simultaneously backward at the past and forward to the future. A silent moon exists in the deep silence of winter earth after the solstice celebration, heralding the birth of energy and the return of ever-lengthening daylight.

This is a time for stillness. The quality of this moon’s energy is vivid.

Silent Moon was commissioned by, and is dedicated with admiration and gratitude to, Almita and Roland Vamos. The duration of this work is eight minutes and is in three movements played without a pause. The music goes full cycle, coming back to its exact starting point, as if we hear one orbit.

The three movements are:

I: Still: Soulful and Resonant

II: Energetic: Majestic and Dramatic

III: Suspended: Lyrical and Chant-like — “When twofold silence was the song of love.”

—Program Note by Augusta Read Thomas

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born 1756, Salzburg

Died 1791, Vienna

Divertimento in F Major, K.138

Mozart wrote three “divertimenti” for strings, K.136-8, in Salzburg in 1772, but a certain amount of mystery continues to surround this music. The designation “Divertimenti” in the manuscript is not in Mozart’s hand, and these three pieces lack the minuet movements characteristic of the divertimento form. Even the size of the instrumental forces Mozart had in mind is unclear: Although scored for four string instruments, these works may be played by either quartet or string orchestra.

Mozart biographer Alfred Einstein has suggested that these three works, composed after Mozart’s second trip to Italy, may have been written for use during his third Italian tour late in 1772 and that the simple addition of horns and oboes would transform these quartet-like works into symphonies on the three-movement Italian model. Mozart may have extracted double service from these pieces: as divertimentos for string quartet in Salzburg and as potential symphonies intended for the court of Milan, where he had been feted during previous tours. The uncertainty about the form of these works has led to their being classified variously (and erroneously) as the “Salzburg symphonies” and “quartet-symphonies.”

The last of the three, Divertimento in F Major, K.138, is a jewel: a fully formed string symphony only nine minutes long. In its grand gestures and rich sonorities, this music certainly sounds symphonic. The sonata-form opening movement (Mozart left no tempo indication) opens with a two-part theme—the powerful opening figure and its soft “answer” —followed by a flowing main idea announced and decorated by the two violin sections. This is followed by a moving Andante, in which the16-year-old composer offers music whose haunting lyric lines foreshadow the great slow movements of his final years. The Presto is a sparkling rondo, complete with two contrasting episodes: the chirping second and a coda. This polished finale sizzles past in only 100 seconds.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

LISA MARIE STUART

LISA MARIE STUART

Born 1966, Albuquerque, NM

Tabula Rasa

Lisa Marie Stuart is a cellist with over 35 years of experience as a musician, performer and composer. She is the owner of Cello Girl Music Instruction and is a teacher of violin, viola, cello, guitar and ukulele. Lisa performs in the cello and harp duo Marigold Sound. She is also a multimedia children’s book author, and she composed and recorded audio soundtracks for her books “The Little Cat, the Wonderful Witch & the Clever Mouse”, and “No Witches Allowed”.

“I composed this string quartet during the height of the pandemic. It was a commission, and I was asked to compose a piece with the theme of ‘rising from the pandemic.’ While I was composing, I had some difficulty envisioning what it would be like for the pandemic to actually be over. It just seemed to be getting worse every day—with new, deadlier strains of the virus emerging.

When I finished composing the opening theme, I decided it was time to choose a name for the piece, and I called it Tabula Rasa, which means ‘Clean Slate.’ Then I continued composing the piece as if it was a prayer for a clean slate; a prayer to end all of the of the fear, sorrow, and grief I was witnessing around me and for life to be normal again, but with a fresh new outlook.

Now that we have finally risen from the pandemic, sit back, relax, and interpret the music according to your own personal experience. Allow the music to heal you!”

—Program Note by Lisa Marie Stuart

PHILIP GLASS

Born 1937, Baltimore

String Quartet No. 2, “Company”

In 1980, Samuel Beckett published a novel called Company in which an old man, lying on his back in the dark, is assailed by a voice that comes out of that darkness. The voice knows him, recalls events from his life, describes them, and calls into question his ability to remember and to know himself–it is not so much a matter of a man confronting his past as of his being confronted by fragments of that past, and challenged to try to make sense of them.

Several years later, the New York theater group Mabou Mines presented (with Beckett’s permission) a staged version of the novel. With so little action in the traditional sense, the “dramatic” version made notable use of staging and lighting, and director Fred Neumann asked Philip Glass (who had been associated with Mabou Mines for years) to provide music to accompany the production. Glass scored the music for string quartet and divided it into four brief movements that functioned as an introduction and musical interludes during the course of Company. While the music is somber, dark, and heavily atmospheric, it is difficult to call this “incidental music,” for it is in no sense representational. The four movements have no names (Glass titles them only with Roman numerals), nor do they correspond to events in the play. This is abstract music built on the pulsing, repetitive rhythms typical of Glass’ music. The quartet is sometimes heard in an arrangement for string orchestra, but in either version it conveys some of the dark condition of Becket’s vision.

–Program Note by Eric Bromberger

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Born 1809, Hamburg

Died 1847, Leipzig

String Quartet in A Minor,op.13

Mendelssohn never met Beethoven—he had grown up in northern German cities, far from Vienna, where Beethoven lived the final 35 years of his life. But the young composer regarded Beethoven as a god. Only months after Beethoven’s death in March of 1827, Mendelssohn wrote his String Quartet in A Minor. This quartet seems obsessed by the Beethoven quartets, both in theme-shape and musical gesture, and countless listeners have wondered about the significance of these many references.

The piece (written when Mendelssohn was only 18) opens with a slow introduction. This Adagio, which evokes memories of Beethoven’s Quartet in A Minor, op.132, also quotes one of Mendelssohn’s own early love-songs, “Ist es wahr?” and that song’s principal three-note phrase figures importantly in the first movement. The music leaps ahead at the Allegro vivace, and Mendelssohn’s instructions to the players indicate the spirit of this music: agitato and con fuoco. The second movement also begins with a slow introduction, an Adagio that has reminded some of the Cavatina movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in B-flat Major, op.130. The main body of the movement is fugal, based on a subject that appears to be derived from Beethoven’s String Quartet in F Minor, op.95.

The charming Intermezzo is the one “non-Beethoven” movement in the quartet. In ABA form, it opens with a lovely violin melody over pizzicato accompaniment from the other voices; the center section (Allegro di molto) is one of Mendelssohn’s fleet scherzos, and he combines the movement’s principal themes as he brings it to a graceful close. The sonata-form finale opens with a stormy recitative for first violin that was clearly inspired by the recitative that prefaces the finale of Beethoven’s String Quartet in E-flat Major, op.127. Not only does Mendelssohn evoke the memory of several Beethoven quartets in this finale, but at the very end he brings back quotations from this quartet’s earlier movements: The fugue subject from the second movement is heard briefly, and the quartet ends with the heartfelt music that opened the first movement.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger