Program Notes | Sounds of the Season

Sunday, Dec 11, 2022 / 4:00 pm

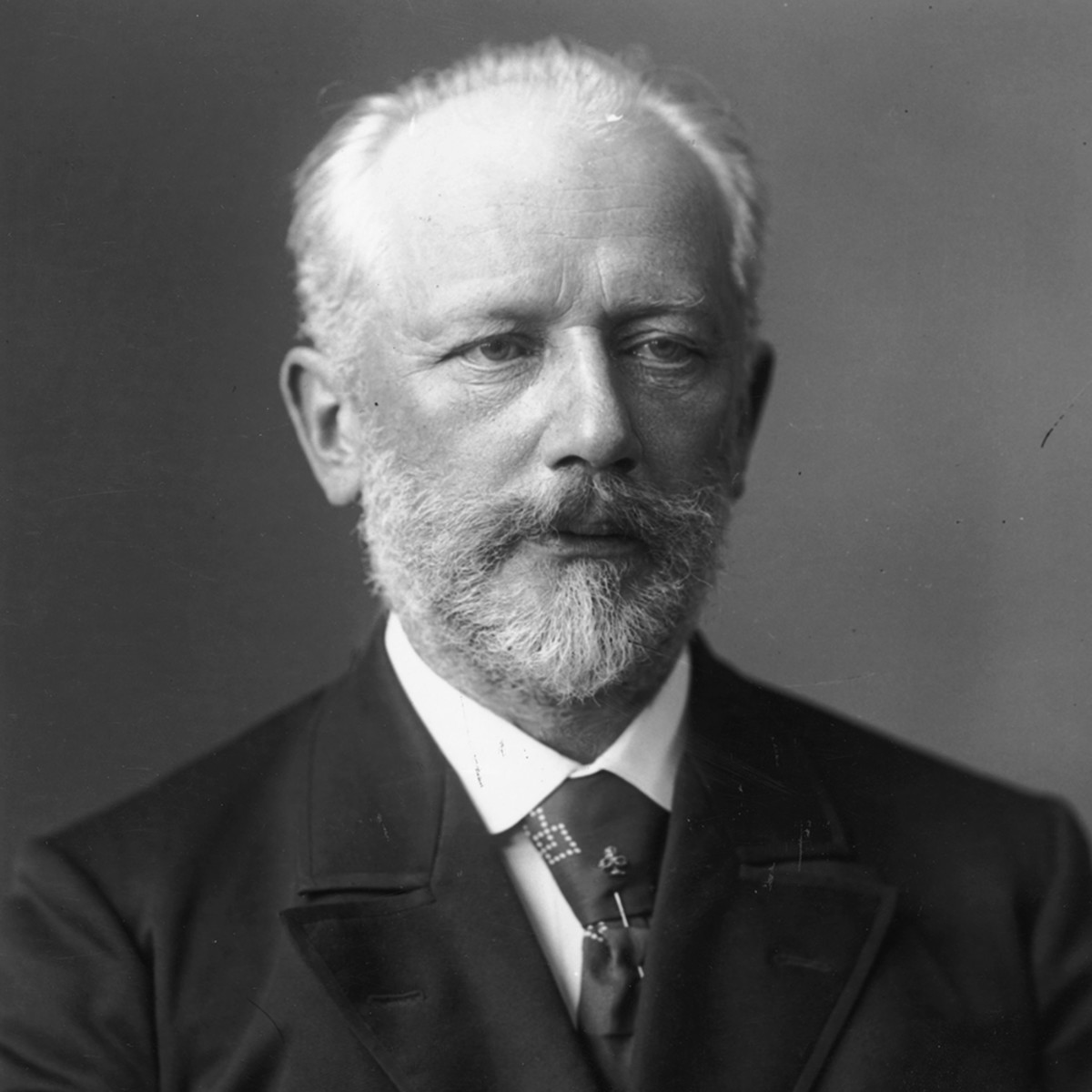

PETER ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY

PETER ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY

Born May 7, 1840, Votkinsk

Died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg

Selections from The Nutcracker Suite

Early in 1891, the Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg approached Tchaikovsky with a commission for a new ballet. They caught him at a bad moment. At age 50, Tchaikovsky was assailed by worries that he had written himself out as a composer, and—to make matters worse—they proposed a story line that the composer found unappealing: They wanted to create a ballet on the old E.T.A. Hoffmann tale Nussknacker und Mausekönig, but in a version that had been retold by Alexandre Dumas as Histoire d’un casse-noisette and then furthered modified by the choreographer Marius Petipa. This sort of Christmas fairy tale full of imaginary creatures set in a confectionary dream-world of childhood fantasies left Tchaikovsky cold, but he accepted the commission and grudgingly began work.

Then things got worse. He had to interrupt work on the score to go on tour in America (where he would conduct at the festivities marking the opening of Carnegie Hall), and just as he was leaving his sister Alexandra died. The agonized Tchaikovsky considered abandoning the tour but went ahead (it was a huge success), and then returned to Russia in May and tried to resume work on the ballet. He hated it, and—probably more to the point—he hated the feeling that he had written himself out as a composer. To his brother, he wrote grimly: “The ballet is infinitely worse than The Sleeping Beauty—so much is certain.” The score was complete in the spring of 1892, and The Nutcracker was produced in at the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg that December, only eleven months before the composer’s death at 53. At first, it had only a modest success, but then a strange thing happened—that success grew so steadily that in the months before his death Tchaikovsky had to reassess what he had created: “It is curious that all the time I was writing the ballet I thought it was rather poor, and that when I began my opera [Iolanthe] I would really do my best. But now it seems to me that the ballet is good, and the opera is mediocre.”

Tchaikovsky may have suspected—in the months before his premature death—that The Nutcracker would prove a success, but he could have had no idea just how popular it would prove: Over the last century The Nutcracker has become an inescapable part of our sense of Christmas, and the current catalog lists nearly 40 recordings of the familiar Suite. This concert offers not that familiar Suite but a selection of movements from the ballet, largely characteristic dances. The fiery Russian Dance (sometimes called Trepak) is a wild Cossack dance, while La mère Gigogne (roughly equivalent to The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe) features dancing clowns. Tchaikovsky, who was an admirer of Johann Strauss, loved waltzes, and this selection concludes with one of his finest, The Waltz of the Flowers from Act II of The Nutcracker.

We hear such music and are left wondering: How possibly could the man who wrote it have worried that he had dried up as a composer?

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

IRVING BERLIN

IRVING BERLIN

Born Tyumen, Russia

Died 1989, New York City

White Christmas

Born in Russia, Israel Baline came to this country with his family at age five. He began writing songs as a boy and published his first at age 19. Four years later, under the name Irving Berlin, he achieved fame and wealth with the song Alexander’s Ragtime Band and went on to become one of the most characteristic American voices of the 20th century: Estimates of the number of songs he wrote run as high as 1500. Many of these—songs like God Bless America, There’s No Business Like Show Business, and This Is the Army, Mr. Jones—have become part of the American national identity.

White Christmas was originally part of Berlin’s score for the 1942 film Holiday. The mellow sound of Bing Crosby’s voice was perfectly suited to this song, with its warm but relaxed sentiment, and White Christmas—in its many reincarnations—has become an inescapable way we think of that holiday. Its popularity has never been in doubt: White Christmas won the Academy Award as the best song of 1942.

―Program note by Eric Bromberger

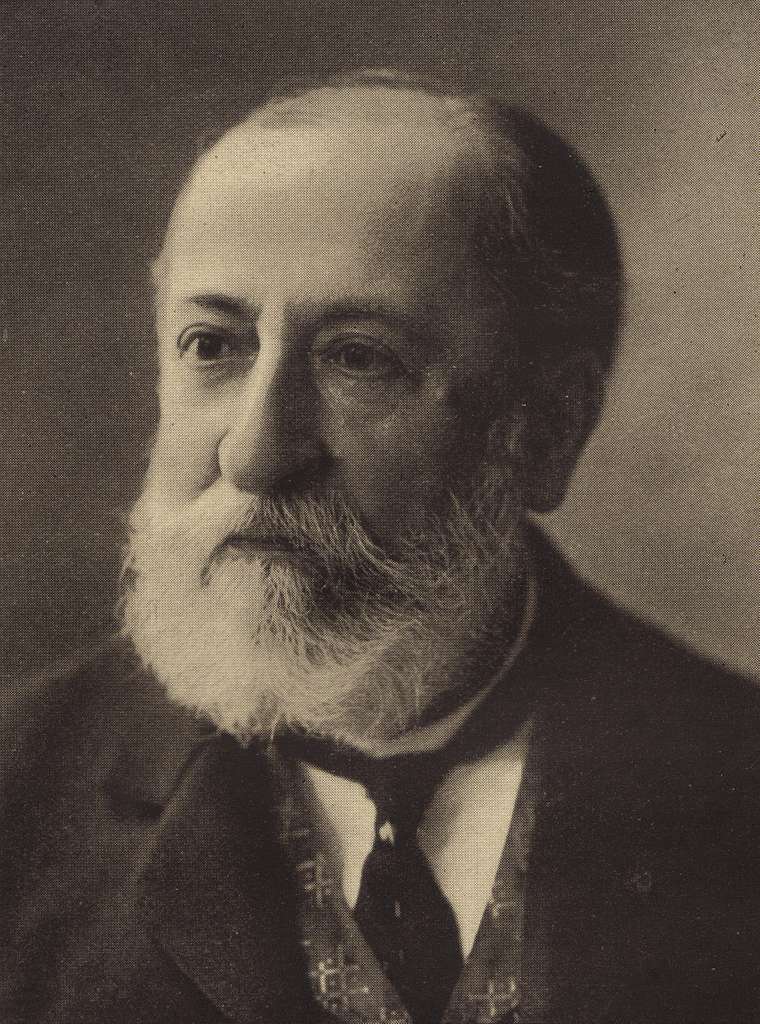

CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS

Born 1835, Paris

Died 1921, Algiers

Bacchanale from Samson et Dalila, op. 47

Saint-Saëns had a difficult time with his opera based on the story of Samson and Delilah, from the book of Judges. He originally planned it as an oratorio and set to work in the late 1860s, but he was soon convinced to recast it an opera. When parts of the opera were performed, however, they provoked strong criticism. Worse, the Paris Opera refused to perform an opera based on a Biblical subject.

Samson et Dalila might have gone unperformed, but Saint-Saëns’ good friend Franz Liszt saw the score, admired it, and arranged a production in Weimar. That performance on December 2, 1877 (in German) was a huge success, but the Paris Opera remained adamant in its objections and refused to stage the opera until 1890. By the time of his death in 1921, however, Saint-Saëns had the satisfaction of knowing that the Paris Opera had performed Samson et Dalila more than 500 times.

One of the most famous parts of the three-act opera is the Bacchanale, which is heard in its final scene. After being seduced by Dalila, Samson has been blinded, his hair shorn, and he has been shackled and forced to turn a mill-wheel as he laments his failure to protect his people. The Philistines celebrate their triumph over Samson with a wild dance. A bacchanale is not a musical form but rather an event; it has been described as a wild drinking party—the term comes from Bacchus, the Roman god of wine.

Saint-Saëns had traveled extensively through northern Africa and the Middle East, and he adapted the idiom of the music of that region for his Bacchanale, with its evocative oboe solo at the opening and the wild energy of its dances. The Bacchanale is infectious music, built on a series of crisp tunes, all projected in an energetic 2/4 meter. This music marks the final moments of the Philistines’ triumph: Samson will shortly summon his strength and bring the temple tumbling down upon them all.

LEROY ANDERSON

LEROY ANDERSON

Born 1908, Cambridge, MA

Died 1975, Westbury, CT

Sleigh Ride

Leroy Anderson is best remembered for his lighter music intended for pops concerts, pieces like The Syncopated Clock, Fiddle-Faddle, The Typewriter, Blue Tango, and Plink, Plank, Plunk! His Sleigh Ride has become an inescapable part of the way we observe Christmas, and its infectious rhythms and pleasing tunes can be heard in every shopping mall in this country during the holiday season.

The story behind this famous music is an interesting one. During World War II, Anderson served as a translator for the army in Iceland. There was a housing shortage after the war as veterans returned from overseas, and Anderson, his wife, and their infant daughter had to move into a cottage in Woodbury, Connecticut, that was owned by his mother-in-law. It was in that cottage, during a heat wave in July 1948, that Anderson composed Sleigh Ride, perhaps in part as a way of escaping the heat. The composer noted that the entire piece is based on the steady rhythm of sleigh bells, and over that rhythm he offers a couple of perky, happy tunes that seem perennially to catch some of the fun of the Christmas season. Anderson composed Sleigh Ride purely as an orchestral piece, but two years later Mitchell Parish added words, and the music is sometimes heard in that version.

―Program note by Eric Bromberger

GERÓNIMO GIMÉNEZ

GERÓNIMO GIMÉNEZ

Born 1854, Seville

Died 1923, Madrid

La Boda De Luis Alonso

By the age of 12, Gerónimo Giménez was already playing in the first violin section of the Teatro Principal orchestra in his native Cadiz. A genuine prodigy, he became the director of an opera company five years later. In 1874, he enrolled at the Paris Conservatory, where he studied violin and composition. He traveled to Italy after graduation but soon returned to Spain, where he settled in Madrid. In 1885 he became director of the Teatro Apolo de Madrid and later the Teatro de la Zarzuela.

Giménez’s music has been cited as an influence on such Spanish notables as Joaquin Turina and Manuel de Falla. La Boda de Luis Alonso is a short-form zarzuela, a characteristic Spanish popular entertainment style of work that often includes singers and dancers. The title translates to “The Marriage of Luis Alonso.” The intermezzo from the piece demonstrates the ebullient energy of the Spanish showpiece tradition; there’s no question of where this music originated.

—Program notes by R. M. Teplitz