Program Notes | The Planets

Sunday, October 15, 2023 / 4:00 pm

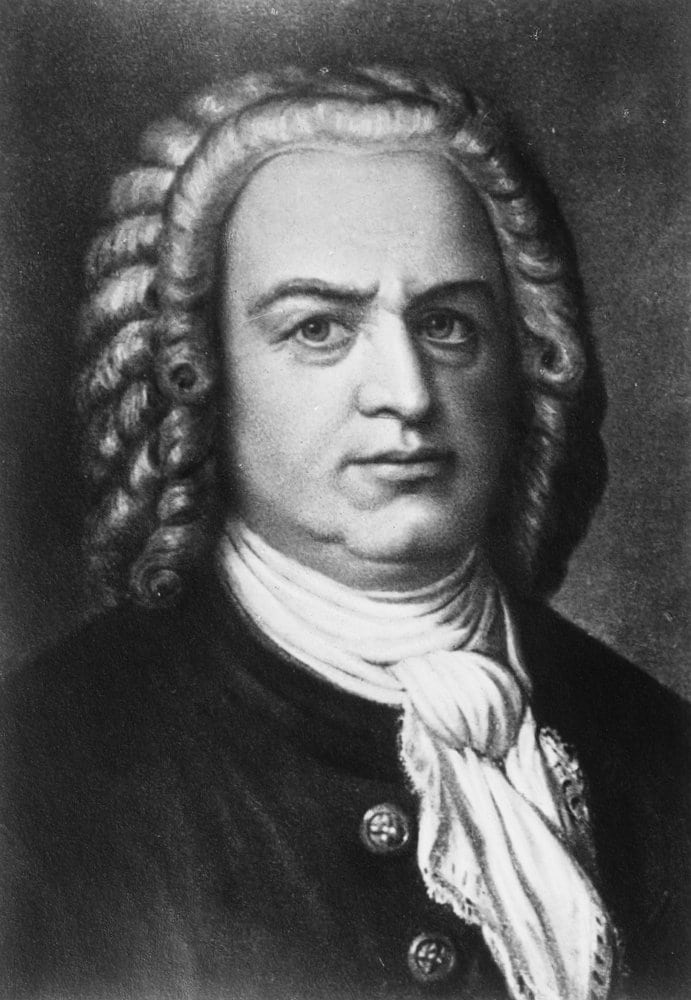

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Born 1685, Eisenach, Germany

Died 1750, Leipzig

Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins in D Minor, BWV 1043

This ever-popular concerto dates from about 1720, or the middle of Bach’s six years as music director to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. The work (also known as the Double Concerto) is a favorite of all violinists, from the greatest virtuosos to the humblest amateurs, and it is easy to understand why: It offers pleasing melodies, an even distribution of duties between the soloists, and one of Bach’s greatest slow movements.

The opening movement is significantly marked Vivace rather than the usual Allegro; Bach’s marking stresses that he wants a lively performance, vivacious rather than simply fast. A long orchestral introduction presents the main theme, and soon the solo violins enter, gracefully trading phrases. Though it moves smoothly and easily, this music is much more difficult than it sounds, requiring wide melodic skips and awkward string-crossings. The solo exchanges are interrupted by orchestral tuttis in a manner reminiscent of the concerto grosso (to which the concerto bears a strong resemblance), and at the end the orchestra brings the movement to a powerful close.

The real glory of this concerto comes in the slow movement (Largo, ma non tanto) which is nearly as long as the outer movements combined. The second violin sings the noble melody that will dominate this movement, then accompanies the first violin as it enters with the theme. This balanced partnership extends throughout the movement, each violin spinning out Bach’s gloriously poised melodic lines one moment, turning to accompany the other the next.

By contrast, the concluding Allegro bristles with energy, hurtling along on a steady flow of sixteenth-notes. This movement is more varied rhythmically than the first; the soloists have sudden bursts of triplets and break out of the orchestral texture to launch their own soaring melodies. The orchestra’s vigorous tuttis punctuate the movement and bring it to a vigorous close.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

HENRYK WIENIAWKSI

HENRYK WIENIAWKSI

Born 1835, Lublin

Died 1880, Moscow

Violin Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp Minor, op.14

By all accounts, Polish-born Henryk Wieniawski was one of the greatest of all violinists: His beautiful sound, perfect technique, and sensitive musicianship impressed all who heard him play. His life reads like something out of a storybook account of what a prodigy should be. He entered the Paris Conservatory at age 8, won the first prize for violin at 11, was given a Guarnerius violin by the emperor, and made a brilliant–if brief–career as a virtuoso violinist. He toured throughout Europe but settled in St. Petersburg, where he was soloist for the czar and concertmaster of the court orchestra from 1860 until 1872. In that last year, he and Russian pianist Anton Rubinstein embarked on a long tour of the United States, giving 216 concerts in 245 days. When the exhausted Rubinstein abandoned the tour, Wieniawski continued by himself, eventually reaching California. He returned to Europe and became professor of violin at the Brussels Conservatory, but a heart condition and declining strength forced him to give up that position. He died at 44, two months before the birth of his youngest daughter.

As might be expected, Wieniawski wrote almost exclusively for the violin, and some of his works, including the Second Violin Concerto and the Scherzo-Tarantelle, remain important parts of the repertory. While Wieniawski’s Second Concerto has become famous, his First remains much less wel -known, though it has had important champions, including Itzhak Perlman and Michael Rabin. Wieniawski composed it in 1852, when he 17 years old. He gave the premiere with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra on October 27, 1853, and dedicated the concerto to King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, a generous patron of the arts.

The First Violin Concerto is in the expected three movements in a fast-slow-fast sequence, and it gets off to a surprising beginning in which only the woodwinds play. Cellos sing a flowing second theme before the violin makes a spectacular entrance: playing fingered ninths (an octave plus two intervals), and from here on the writing for violin is of hair-raising difficulty: spiccato runs, harmonics, double-stopped passages, and all manner of violinistic fireworks. The lengthy cadenza is even more difficult, and those difficulties continue after the orchestra returns.

The mood changes completely in the second movement, Preghiera (“Prayer”). A solemn orchestral introduction leads to the soloist’s entrance, and now the writing for violin, which had been so brilliant in the first movement, goes almost to the other extreme. The violin’s line is simple, and the emphasis here is on beauty of sound and expression. This movement proceeds without pause into the finale, which is a rondo marked Allegro giocoso (“Fast, happy”). Brass fanfares lead the way, and the violin quickly enters on the dancing theme that will form the backbone of this movement. A relaxed second episode brings some contrast, but the violin’s energetic dance makes a welcome return through the fiery coda.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

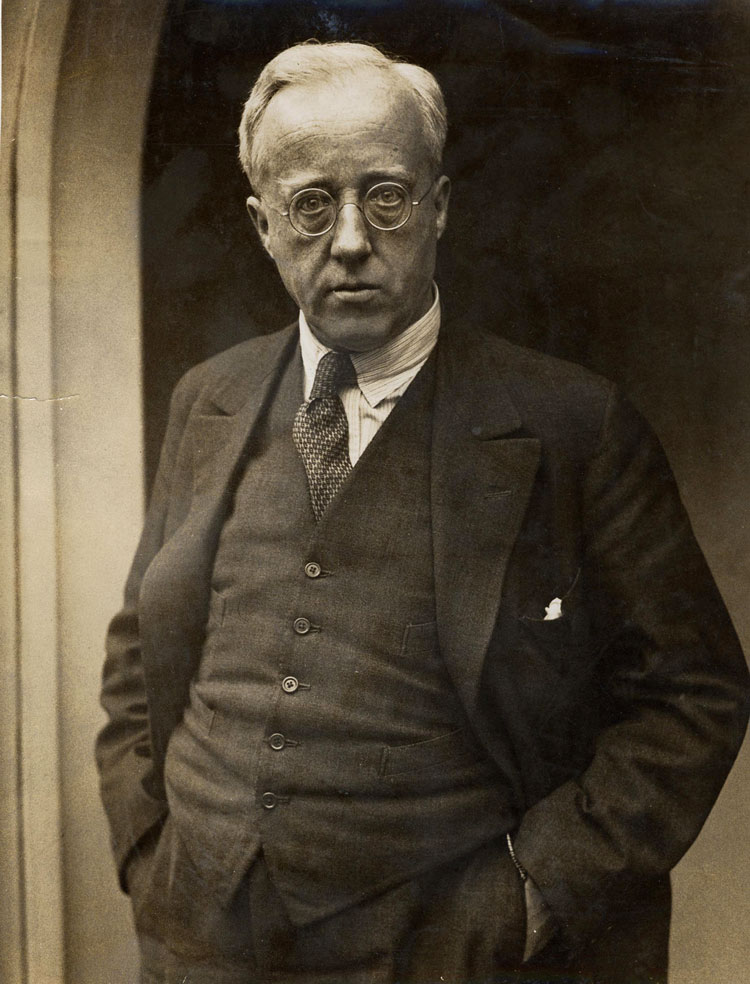

GUSTAV HOLST

GUSTAV HOLST

Born 1874, Cheltenham, England

Died 1934, London

The Planets,op.32

Mystic, visionary, and socialist, Gustav Holst was also fascinated by astrology, and that passion helped shape The Planets. Holst composed this suite for large orchestra during the years 1914–16, when he was teaching at St. Paul’s Girls School in Hammersmith, a borough of London. The name The Planets can be misleading, and Holst’s intentions in this work need to be understood carefully.

When he began composing this work, Holst was convinced that he would never be able to arrange a performance, so rather than feeling constrained by the limits of a normal symphony orchestra, he added many unusual instruments. The piece calls for an orchestra of four flutes, two piccolos, bass flute in G, three oboes, English horn, three clarinets, bass clarinet, three bassoons, contrabassoon, six horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tenor tuba, bass tuba, two harps, celeste, organ, six timpani, a massive percussion battery (triangle, side drum, tambourine, cymbals, bass drum, gong, bells, glockenspiel, and xylophone), plus the usual strings. Fortunately, Balfour Gardiner, a wealthy patron of the arts, learned of this score and arranged a private performance with a professional orchestra. On September 29, 1918, Holst heard this music come to life for the first time.

Although each of the seven movements has the name of a planet (Holst did not use Earth, and Pluto was not discovered until 1930), Holst did not want to depict the planets themselves. Instead, he was interested in the names of the planets and the associations that went with them, particularly their astrological associations:

Mars, the Bringer of War: An insistent 5/4 meter, tapped out by the wood of the bows, opens the movement and continues throughout. Trumpet calls announce the arrival of the god of war, and his violence saturates this entire movement, rising to the massive chords that bring it to a grinding close.

Venus, the Bringer of Peace: The pure, cool, and precise music brings complete contrast, a draught of clear water after the fire and smoke of the opening movement. Silvery violin solos contribute to the mood of calm.

Mercury, the Winged Messenger: Although third in the suite, this scherzo was the last movement to be composed and is musically the most complex. Holst mixes meters and tonalities daringly: For example, the first and second violin sections play in different keys.

Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity: Holst is more earthbound in his intentions here, describing his Jupiter as “one of those jolly fat people who enjoy life.” The movement is in rondo form, and at the center comes a stately melody that has become a symbol of English pomp and ceremony (Holst later used this tune to set the text “I Vow to Thee, My Country”).

Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age: This movement, Holst’s favorite, opens with eerie, empty chords and soon leads to madly tolling bells that signal the passage of time, but a noble chorale for trombones (Holst’s own instrument) establishes a mood of acceptance and serenity.

Uranus, the Magician: One of the most brilliant sections of the suite, Uranus has been compared to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, although Holst did not know Dukas’ music when he wrote The Planets. Here is a portrait of a magician going through all his tricks: The movement opens with a four-note motto that will recur in many forms. Near the end, the magician vanishes in a puff of smoke, the motto thunders out, and the music ends in silent mystery.

Neptune, the Mystic: Holst takes an artistic risk here, choosing to end quietly after all the brilliance that has preceded the movement. Mysterious swirls of sound hover at the edge of this solar system, and the orchestra remains at a pianissimo dynamic throughout. At the end, a six-part women’s chorus sings a wordless text offstage, repeating the final measure until, in Holst’s words, “the sound is lost in the distance” and the audience is left at the silent edge of infinite space.

―Program Note by Eric Bromberger