Program Notes | A Night at the Opera

Saturday, December 24, 2022 / 5:00 pm

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born 1756, Salzburg

Died 1791, Vienna

Overture to The Marriage of Figaro, K.49

In many respects, The Marriage of Figaro marked the high point of Mozart’s success during his lifetime. On a visit to Prague the following year to conduct the opera, Mozart reported that “Here nothing is talked of but Figaro, nothing played but Figaro, nothing whistled or sung but Figaro, no opera so crowded as Figaro, nothing but Figaro.”

Mozart customarily composed the overtures to his operas last, so that was likely the case with Figaro. Mozart’s overtures were usually in sonata form, but he abandoned that form here, and for good reason. Figaro is witty, brilliant and wise, and it needs an overture that will quickly set its audience in such a frame of mind. This overture is very brief (barely four minutes), and Mozart drops the development section altogether. He simply presents his six sparkling themes, recapitulates them, and plunges into the opera. From the first instant when this music stirs to life to its sudden explosions of energy, the overture is the perfect lead-in to the comic escapades that will follow.

Opening Duet to Act I

The Marriage of Figaro is one of the oldest operas in the standard repertoire and one of the most youthful in spirit. When Beaumarchais’s play, on which the opera is based, was published in 1782, its unflattering portrait of the upper classes understandably caused a scandal that horrified King Louis XVI. The play was banned, but like any scandal, it proved irresistible to the public. The opera to Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto premiered four years later. In Vienna, the court wasn’t particularly happy with it either.

In the opening scene of the opera, the duet is sung by Figaro, personal valet to Count Almaviva; and his bride-to-be Susanna, a maid to countess Rosina. They try to find space in their room for their furniture—especially the bridal bed. There is a worrying undertone in the duet, since the room is adjacent to that of the predatory Count with his roving eyes—and roving hands.

—Program Notes by Eric Bromberger

GIOACHINO ROSSINI

GIOACHINO ROSSINI

Born 1792, Pesaro

Died 1868, Passy

Ecco, ridente from The Barber of Seville

It is hard to understand today why the February 1816 premiere of The Barber of Seville in Rome was such an unmitigated disaster. True, the popular overture we know today was originally not part of the opera, and another opera called The Barber of Seville by Giovanni Paisello, although dated, was already considered a classic in Italy. But the simple ebullience and mischievousness of Rossini’s Opera buffa did not deserve the vituperation and hostility it encountered.

In the United States, The Barber of Seville premiered in New York in May 1819, but in English. In November 1825, it was performed again: This time, it was the first performance in America of opera in Italian.

In this scene, as the curtain rises, it is shortly before dawn and Count Almaviva is preparing to serenade Rosina, the ward of the old and pompous Dr. Bartolo. He has followed her, disguised as the student Lindoro, because he doesn’t want her to marry him solely for his title and money. Aided by his servant Fiorello and a band of hired musicians, he serenades her with Ecco, ridente in cielo (Here, laughing in heaven), a musically eloquent but strategically ineffective venture. Frustrated by Rosina’s lack of response, Almaviva pays off the musicians and determines to keep vigil alone.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

RICHARD STRAUSS

RICHARD STRAUSS

Born 1864, Munich

Died 1949, Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Ariadne auf Naxos

Sie hält ihn für den Todesgott

Sein wir wieder gut

Ariadne auf Naxos has one of the most convoluted histories—not to mention a convoluted plot—in operatic history. It was originally conceived as a one-act piece by Strauss’ exclusive librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, to follow a German adaptation of Molière’s 17th-century comedy Le bourgeois genitlhomme. It was supposed to include incidental music by Strauss, but the work was unwieldy to produce, lasted six hours and was snubbed by the critics and public.

Meanwhile, Strauss and his librettist wrangled over a total revision, ultimately substituting Molière’s play with an original Prologue—a kind of play-within-a-play—about a composer trying to mount a production of an Italian opera seria (called Ariadne), who is hampered by a troupe of actors from the Commedia dell’arte. Because of ridiculous time constraints imposed by his nouveau riche patron, the composer is obliged to shorten the production drastically and integrate the comedians into the serious opera.

In the duet from the prologue, Sie hält ihn für den Todesgott (She thinks he is the God of Death), the composer and the comedienne Zerbinetta talk and shout at each other at cross purposes, neither really understanding the other—or are they flirting?

In the aria, also from the prologue, the composer sings Sein wir wieder gut (We will be well again), declaring his fervent belief in the great art of music.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

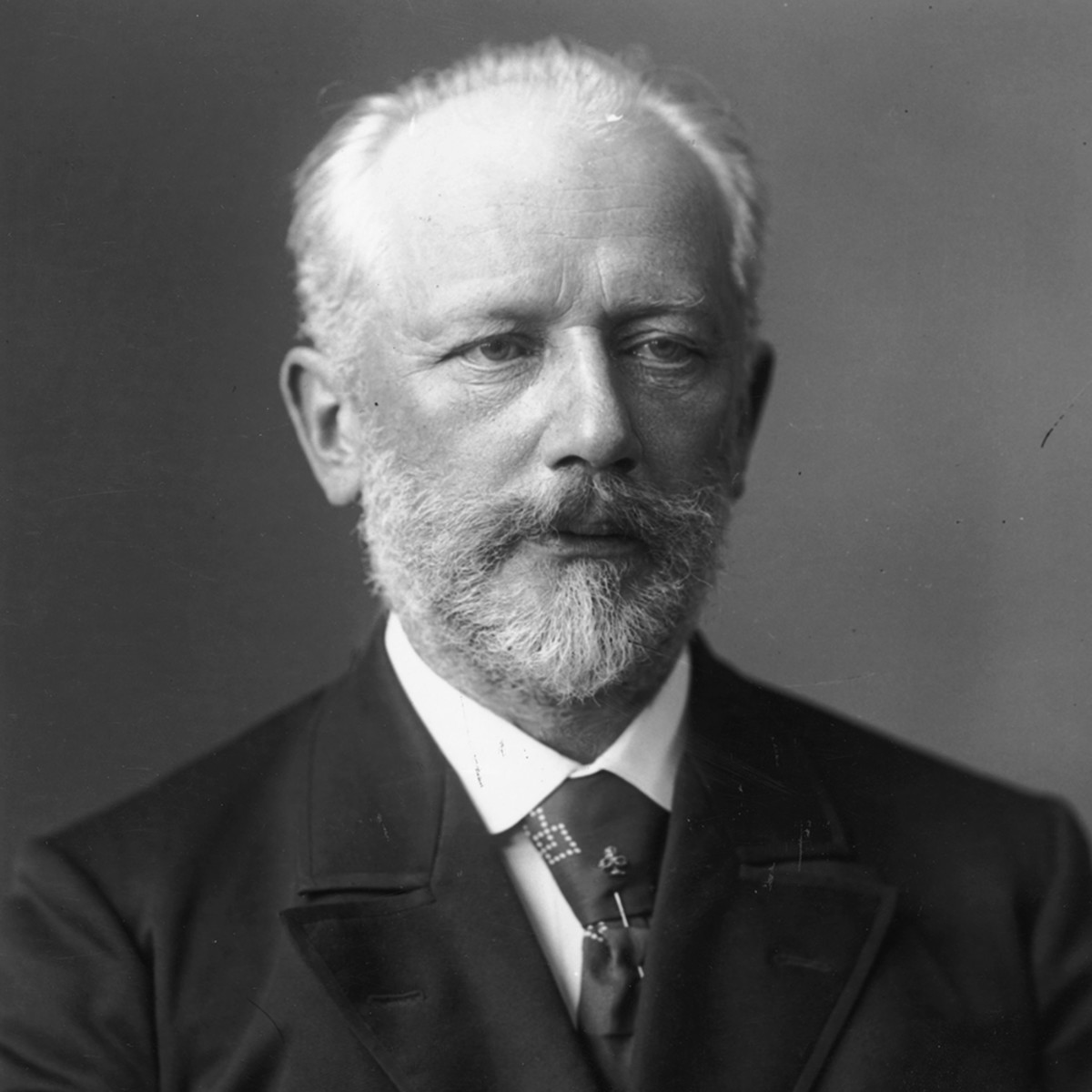

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Born 1840, Votkinsk

Died 1893, Saint Petersburg

Kuda, kuda from Eugene Onegin

Based on Pushkin’s epic poem, Tchaikovsky’s most famous opera tells the common operatic story of love, jealousy and missed chances for happiness. Tatiana is madly in love with Onegin, who rebuffs her and flirts with her sister Olga, the beloved of his friend Lensky. She flirts with him in return, and Lensky, appalled, challenges Onegin to a duel and is killed. Onegin goes into exile, returns after six years and tries to talk Tatiana into eloping with him but she, by then older and wiser, rejects his offer.

Tchaikovsky described Eugene Onegin as lyrical and wanted his performers to concentrate on subtlety of characterization. He chose students to give the premiere, fearing that seasoned opera singers would think their job was only to make a beautiful sound.

In Kuda, kuda (Where have you gone, o golden days of spring), Lensky looks back on his happy youth as he waits for Onegin to arrive. He realizes that he will probably die in the duel and that he does not particularly care if he does. His only regret is that he would never see Olga again.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

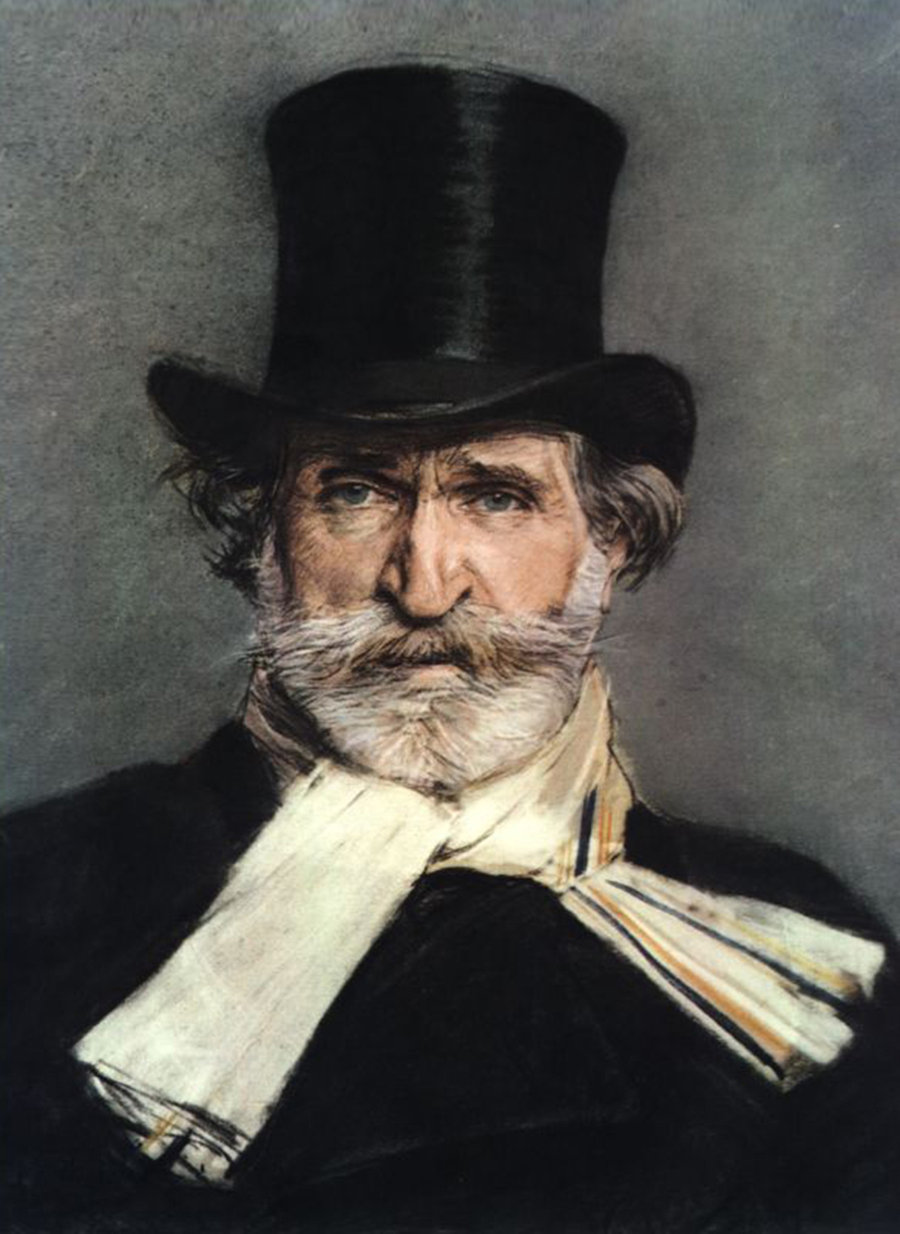

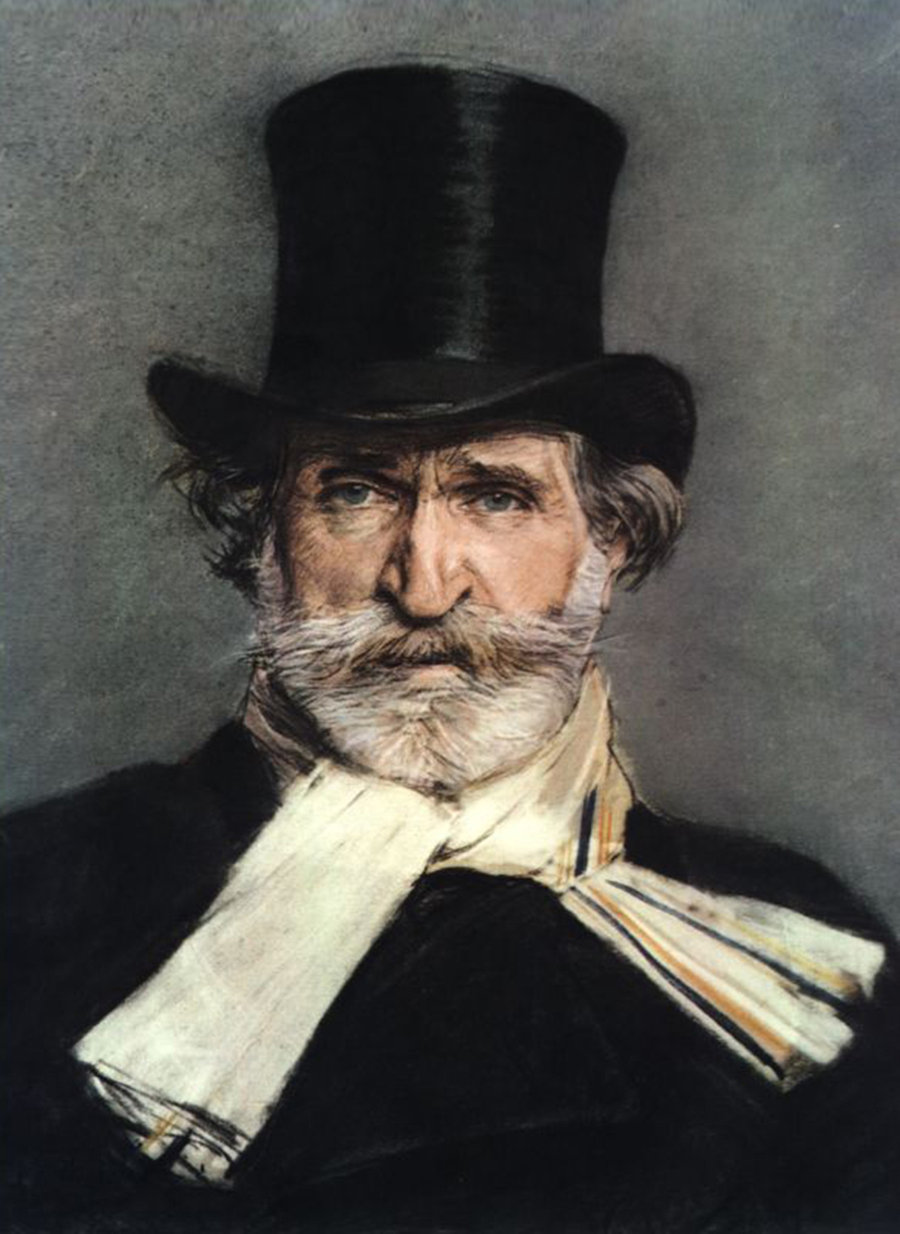

GIUSEPPE VERDI

GIUSEPPE VERDI

Born October 1813, Roncalo

Died 1901, Milan

Brindisi from La Traviata

“A fiasco!” This was the judgment of both composer and audience in March 1853 at the Venice premiere of what is now arguably Verdi’s most popular opera. Already the foremost composer in Italy with 17 operas to his credit—most of them successes—Verdi could afford to expand beyond the artistic conventions of the genre. From its 17th-century roots, serious opera dealt exclusively with mythological or grand historical themes. Verdi’s lifetime interest, however, was the human psyche, regardless of the social rank of the characters. And in La Traviata, he completely broke with tradition.

Based on La dame aux camélias by Alexandre Dumas, a French bestseller of the previous year that was immediately dramatized, La Traviata was the first tragic opera to treat a contemporary subject. Even more scandalizing was the fact that the heroine was a courtesan, and although Violetta Valéry travels only in the best Parisian circles, the word “traviata” means “fallen” or “debauched.” Verdi had also intended that the opera be staged in contemporary dress, an innovation that so disturbed his producer that the composer had to abandon that battle in order to win the war.

Brindisi is a drinking song from Act I, in which the heroine, Violetta, and her ardent admirer and soon-to-be lover, Alfredo, glorify the pleasures of the moment.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

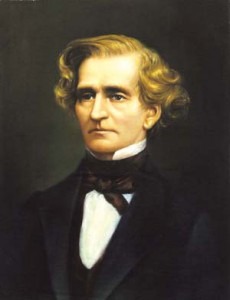

HECTOR BERLIOZ

HECTOR BERLIOZ

Born 1803, La Côte-St-André

Died 1869, Paris

Béatrice et Bénédict

Overture

During the 1850s, Berlioz toured as a guest conductor of his own works, and his concerts in Baden-Baden were particularly successful. As a result, Edouard Bénazet, the owner of the casino and theater in Baden-Baden, commissioned an opera from him, and the composer turned to Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing. Berlioz drew up his own libretto, keeping many lines from Shakespeare but also introducing characters and scenes of his own devising. The result was what Berlioz called “an opéra comique” in two acts.

He took the focus off the potentially tragic relationship between Claudio and Hero, choosing instead to enjoy the battle of the sexes as exemplified by Beatrice and Benedick: The couple may express their disdain for marriage in general and for each other in particular, but they end up married at the happy conclusion of Shakespeare’s play. First produced at Baden-Baden on August 9, 1862, Béatrice et Bénédict enjoyed a successful premiere and was performed several times over the following seasons. Its success was one of the few pleasures of Berlioz’s unhappy final years; he died just a few years later, in 1869.

The opera is seldom staged today because its vast amount of spoken dialogue makes it difficult for opera companies. But Berlioz’s lively overture lives on in the concert hall. It bursts to life on its skittering, playful main theme, which is tossed easily between strings and woodwinds. Berlioz reins in this energy for the solemn second theme-group, marked Andante un poco sostenuto. He simply alternates his themes, embellishes them as they go, and finally drives matters to a grand close on a ringing G-major chord for the whole orchestra. It is a fitting introduction to the tale of love gone wrong (and love gone right) that will follow.

Je vais le voir

The belated discovery of Shakespeare by the French and German Romantics in the early part of the 19th century created an impact nothing short of overwhelming. The French—true to their tradition of dogged adherence to Aristotle’s three unities that required a drama to consume no more than 24 hours, take place in the same location and contain no subplots—modified the plays by such devices as excising scenes of comic relief and forcing the text into Alexandrines (rhyming couplets of twelve syllables).

But for Berlioz, the quintessential Romantic, Shakespeare was the nearest thing to God. By 1860 he had already used two of the plays as models for his music: the dramatic symphony Romeo et Juliette and the overture Le roi Lear. He said about Béatrice et Bénédict, “It is a caprice written with a point of a needle, and requires an extremely delicate performance.”

In Je vais le voir” (I am going to see him), Héro, the daughter of the Governor of Messina, is looking forward to the return of her lover Claudio, aide-de-camp to the Sicilian general, from a victorious battle against an invading Moorish army.

—Overture Program Notes by Eric Bromberger

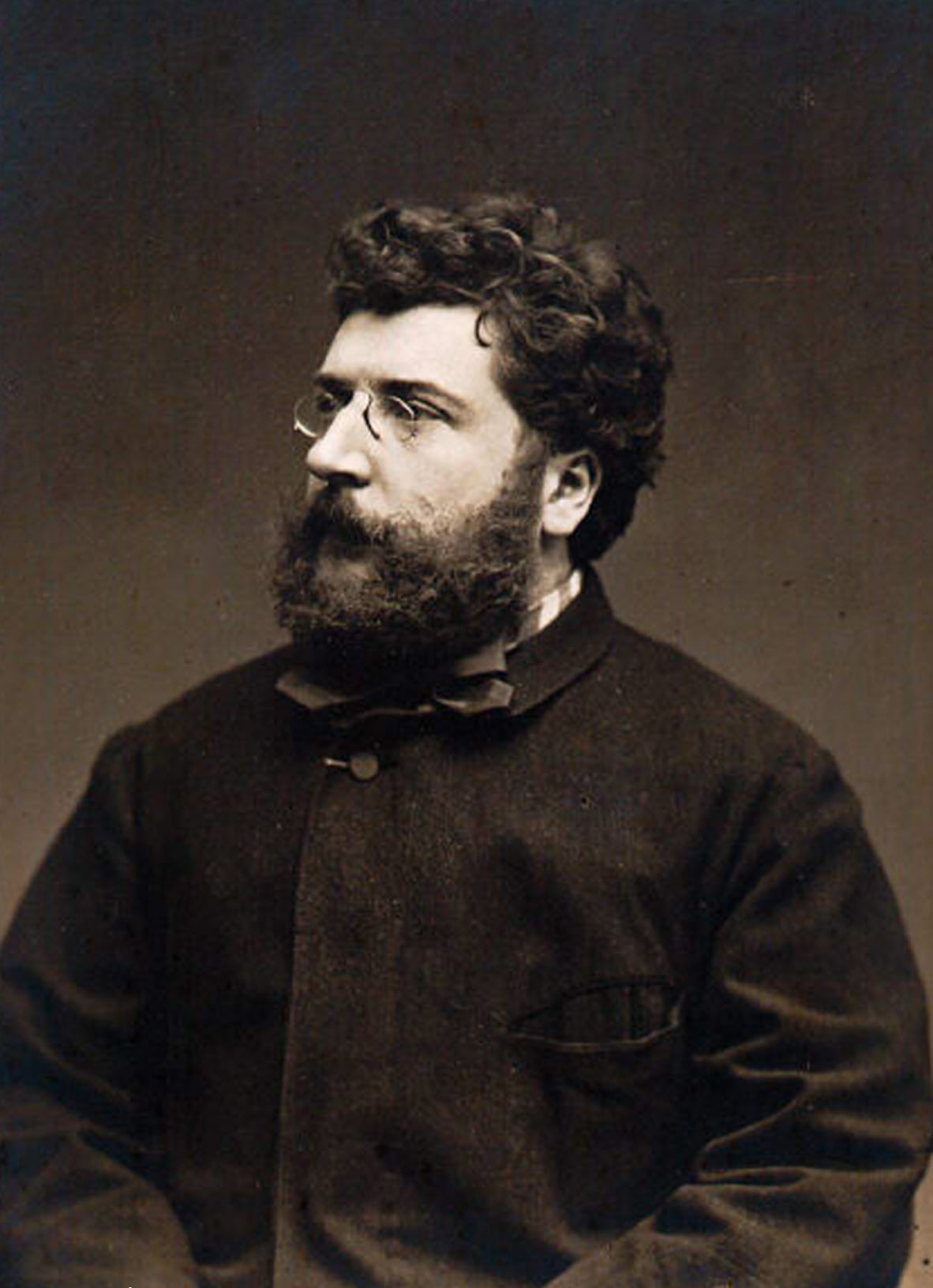

GEORGES BIZET

GEORGES BIZET

Born 1838, Paris

Died 1875, Paris

Votre Toast from Carmen

Georges Bizet was one of those composers who showed precocious brilliance as a child but never lived long enough to completely fulfill the promise. The difference, however, between Bizet and Mozart, who died at about the same age, is that Mozart left more than 600 completed compositions, many of them masterpieces, while Bizet is known primarily for a single work: Carmen.

Based on a contemporary novella by Prosper Merimée, Carmen is the story of a fickle and promiscuous seductress who ensnares an innocent young soldier into a passion that leads inexorably to his desertion, degradation and finally a jealous murder on stage. While other French composers, such as Daniel François Auber and Ambroise Thomas, routinely presented such characters on stage, they were handled discreetly and in accordance with prevailing morality: The guy with the black hat mended his ways, the hero resisted temptation, and the poor but virtuous girl remained virtuous. By contrast, Bizet retained Merimée’s realism, giving the characters darker emotions and poor self-control.

In Votre toast from Act II, the toreador Escamillo struts into the inn with his groupies, singing a rousing aria of self-promotion.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

GIUSEPPE VERDI

GIUSEPPE VERDI

Born October 1813, Roncalo

Died 1901, Milan

Bella figlia dell’amore, Quartet from Rigoletto

Verdi adapted Rigoletto from an already controversial play, Le Roi s’amuse (The King Enjoys Himself) by the scion of French Romanticism, Victor Hugo. The plot centered on the fictional Triboulet, the hunchbacked jester of France’s King François I (1494-1547), whose daughter is seduced and dishonored by the libertine monarch. Hugo’s play was banned in France after its first performance, but the cat was out of the bag: Verdi had been enthusiastic about Hugo’s play for years. In a letter to his librettist Francesco Piave, he wrote: “Le Roi s’amuse is the greatest subject and perhaps the greatest drama of modern times.” The censors did not agree.

In Verdi’s version, Rigoletto, a deformed court jester, mocks the grieving Monterone, whose daughter was seduced by the predatory Duke. Monterone curses Rigoletto for his insensitivity, and in turn the jester’s beautiful daughter Gilda falls prey to the Duke as well. Furious and desperate, Rigoletto hires the assassin Sparafucile to kill the Duke and deliver his body in a sack at the door of a tavern the duke has been frequenting during his nocturnal prowls. But his plan backfires and the curse is fulfilled.

“Bella figlia dell’amore” (Beautiful Daughter of Love) is a quartet from Act III with Rigolatto, Gilda, the Duke and Maddalena. Rigoletto is warning his daughter about the Duke, and Maddalena is trying to lure the Duke to the tavern where her brother is supposed to kill him.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

FRANZ LEHÁR

FRANZ LEHÁR

Born 1870, Komáron

Died 1948, Bad Ischl

Vilja Lied from The Merry Widow

Hungarian composer Franz Lehár is remembered today for his operettas, which were all the rage at the beginning of the 20th century. The best known of these is The Merry Widow, premiered in Vienna in 1905.

The story revolves around Hanna, a rich widow in a small, impoverished Grand Duchy, and the efforts of the Royal Court to keep her money at home by marrying her off to a local aristocrat. The designated groom, the dashing Count Danilo, plays hard to get, but in the end the match is struck.

In Act 2, Hanna sings the sentimental ballad Es lebt’ eine Vilja, ein Waldmägdelein (There was a Vilja, a little forest maiden) to entertain the guests who are celebrating the Grand Duke’s birthday garden party.

—Program notes by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com