Program Notes | Fate and Finale

Sunday, May 7, 2023 / 4:00 pm

EMILIE MAYER

Born 1812, Friedland, Germany

Died 1883, Berlin

Faust Overture, op.46

Very few audiences today know the music of Emilie Mayer, but in the late 19th century she was one of those rarest people—a female composer whose music was performed frequently and admired by critics. Her path to that fame was a difficult one, however. Born into a middle-class family in what is today far northwestern Germany, Mayer lost her mother when she was two, and 26 years later her father shot himself on the anniversary of burying his wife.

Mayer had studied the piano when she was a child, but had never made any effort in the direction of a career in music. Now, perhaps propelled by the family catastrophe, she made the bold decision to study composition. She moved to Stettin (now in Poland) and studied with Carl Loewe, the great singer and composer of songs. Loewe immediately recognized Mayer’s talent, saying “Such a god-given talent as hers has not been bestowed upon any other person I know.” She soon achieved remarkable success when two of her symphonies were performed in Stettin to admiring reviews. In 1847, at age 35, she moved to Berlin to continue her studies with Adolf Bernhard Marx, and three years later an orchestra in that city gave an all-Mayer concert.

Over the remaining three decades of her life she composed, performed and traveled throughout the German-speaking world, and her music was widely admired. Mayer was prolific; her catalog of works includes one opera, eight symphonies, seven overtures, seven string quartets, twelve cello sonatas and nearly 130 songs.

And then . . . her music essentially vanished. Much of it had not been published, performances dwindled, and before long she was forgotten; the 1980 New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians made no mention of her at all. Now, very gradually, her music is being rediscovered, performed and recorded.

The publication of the two parts of Goethe’s Faust (in 1808 and 1832) galvanized composers, who saw in that striving, doomed figure an ideal subject for music. Among the works inspired by that tragic figure were Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust, Wagner’s Faust Overture, Liszt’s Faust Symphony, Gounod’s opera Faust and Schumann’s Scenes from Goethe’s Faust. Emilie Mayer composed her Faust Overture in 1880, when she was 68, and it was premiered in February 1881 in Berlin; further performances followed in Karlsbad, Prague, and Vienna.

Mayer casts her work as a concert overture rather than as a tone poem that “tells” the story of Faust, Mephistopheles and Marguerite: A slow introduction gives way to an Allegro in sonata form based on several different themes, and the overture moves from its dark opening in B minor to a resounding conclusion in B major. But it is tempting to seem to make out certain figures in this abstract music: Is the sinuous introduction a portrait of Mephistopheles? Is the vigorous Allegro a depiction of the striving Faust? Is the lyric secondary material associated with Marguerite? The only clue that Mayer offers comes in the overture’s closing pages: At the moment the music moves from B minor to B major, she writes in the score: Sie ist gerettet (“She is saved”), a reference to Marguerite’s redemption in Part II of Goethe’s Faust. Otherwise, her powerful overture remains abstract, a work inspired by Faust rather than attempting to depict its events in music.

–Program Note by Eric Bromberger

EDWARD ELGAR

EDWARD ELGAR

Born 1857, Worcestershire, England

Died 1934, Worcestershire, England

Cello Concerto in E Minor, op.85

Elgar completed his Cello Concerto in 1919 at a time of great personal distress brought on by his wife’s illness and by the impact of World War I. His Cello Concerto is a work of great beauty and great contradiction. Some of these contradictions rise from the sharp differences of style within the music: Elgar scores the concerto for a large orchestra, but then can use it with a chamber-like delicacy. The mood of the music can move from a touching intimacy one moment to extroverted concerto style the next. We almost sense two completely different composers behind this concerto. One is the public Elgar―strong, confident, declarative―while the other is the private Elgar, torn by age, doubt, and the awful comprehension that all the certainties he had known had been obliterated.

We seem to hear the old, confident Elgar in the cello’s sturdy opening recitative, marked nobilmente, yet at the main body of the movement violas lay out the movement’s haunting main theme, which rocks along wistfully. This somber idea sets the mood for the entire opening movement. Throughout, Elgar reminds the soloist to play dolcissimo and espressivo.

The Allegro molto really flies―it is a sort of perpetual-motion movement, and Elgar marks the cello’s part leggierisimo “as light as possible.” In the Adagio Elgar writes long, lyric lines for the soloist, who plays virtually without pause. The finale at first seems full of enough confidence to knit up the troubled edges of what has gone before. But beneath the jaunty surface of this music, another mood ―dark and uneasy―begins to intrude and finds its clearest expression in the extended Poco più lento section near the end of the music. Gone is the swagger, gone is the confident energy, and we sense that in place of the music Elgar wanted to write, he is giving us the music he had to write. Wandering, pained, dis-eased, this music seems to speak directly from the heart, and even the vigorous concluding flourish does little to dispel the somber mood that has touched so much of this concerto.

―Program Note by Eric Bromberger

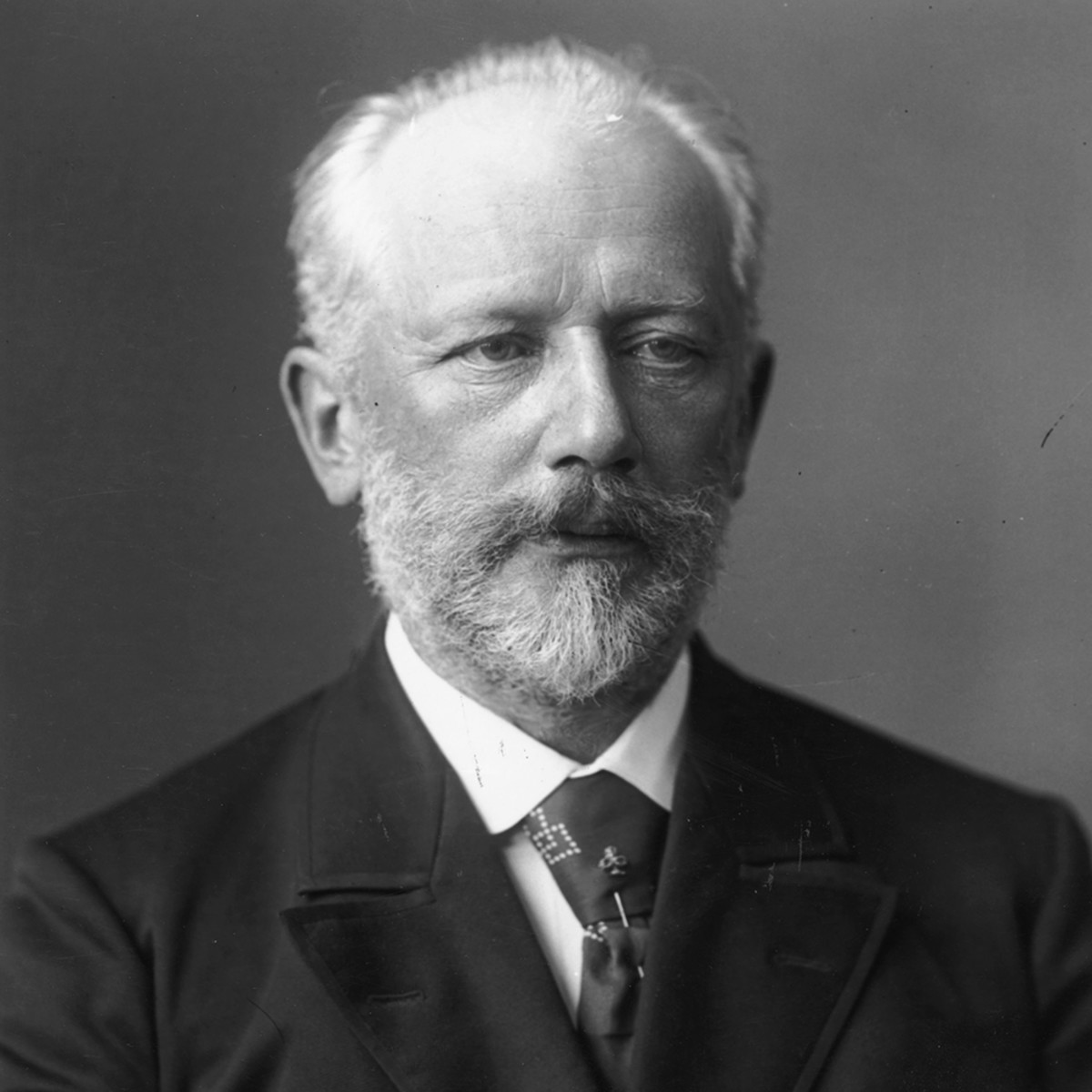

PYOTR ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY

PYOTR ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY

Born 1840, Votkinsk

Died 1893, St. Petersburg

Symphony No. 5 in E Minor, op.64

Tchaikovsky began work on the Fifth Symphony in 1888, after a decade-long creative dry spell that had been precipitated by a nervous breakdown. He had moved into a villa in Frolovskoye, northwest of Moscow, where he could work and take long walks in the woods. He conducted the premiere in St. Petersburg later that year and, despite some initial misgivings, he was finally convinced that he had regained his creative powers.

While it lacks the white-hot fury of the Fourth Symphony or the dark intensity of the Sixth, the Fifth Symphony—full of those wonderful Tchaikovsky themes, imaginative orchestral color, and excitement—has become one of his most popular works, so popular in fact that it takes a conscious effort to hear this symphony with fresh ears. As he did in the Fourth, Tchaikovsky builds this symphony around a motto-theme, and in his notebooks he suggested that the motto of the Fifth Symphony represents “complete resignation before fate.” But that is as far as the resemblance goes, for Tchaikovsky supplied no program for the Fifth Symphony, nor does this music seem to be “about” anything. Tchaikovsky apparently regarded his Fifth Symphony as abstract music.

Clarinets introduce the somber motto-theme at the beginning of the slow introduction, and gradually this leads to the main body of the movement, marked Allegro con anima. Over the orchestra’s steady tread, solo clarinet and bassoon sing the surging main theme of this sonata-form movement, and there follows a wealth of thematic material. This is a lengthy movement, and it is built on three separate-theme groups, full of soaring and sumptuous Tchaikovsky melodies. The development fuses these lyric themes with episodes of superheated drama, and listeners will hear the motto-theme hinted at along the way. With its furious energy finally exhausted, this movement draws to a quiet close.

Deep string chords at the opening of the Andante cantabile introduce one of the great solos for French horn, and a few moments later the oboe has the graceful second subject. For a movement that begins in such relaxed spirits, this music is twice shattered by the return of the motto-theme, which blazes out dramatically in the trumpets. Tchaikovsky springs a surprise in the third movement: Instead of the expected scherzo, he writes a lovely waltz. He rounds off the movement beautifully, with an extended coda based on the waltz tune.

However misty that theme may have seemed at the end of the third movement, it comes into crystalline focus at the beginning of the finale. Tchaikovsky moves to E major here and sounds out the motto to open this movement. This music seems to have arrived at its moment of triumph even before the last movement has fairly begun. The main body of the finale, marked Allegro vivace, leaps to life, and the motto-theme breaks in more and more often as it proceeds. The movement drives to a great climax, then breaks off in silence. But this is a trap, designed to trick the unwary and propel them into premature applause, for the symphony is not yet over. Out of the ensuing silence begins the real coda, and the motto-theme now leads the way on constantly accelerating tempos to the (true) conclusion in E major.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger