Program Notes | One Love, One Planet

Sunday, April 16, 2023 / 4:00 pm

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN

Born 1732, Rohrau

Died 1809, Vienna

Symphony No. 6, “Le Matin” (Morning)

Prince Paul Anton Esterhazy hired Haydn as his Vice-Kapellmeister in May 1761, and the composer immediately took up his duties at the Esterhazy palace in the small town of Eisenstadt, about 30 miles south of Vienna. The old Kapellmeister, Gregor Werner, was being eased upstairs, and the 29-year-old Haydn was charged with revitalizing the court orchestra. He auditioned players (many of whom he knew from Vienna) and assembled an orchestra consisting of flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns and a small string section.

According to lore, the Prince suggested that Haydn compose a trilogy of symphonies that would take as their subject morning, noon and night. Haydn was not attracted to the idea of writing descriptive music, but he was alert enough to take the prince’s suggestion. His real intention in writing these three symphonies, however, may have been to show off his own talents and the orchestra he had helped to create. Haydn gave the three symphonies their French nicknames–Le matin, Le midi and Le soir–perhaps as a nod to the taste for things French in Vienna at that time.

These symphonies, Nos. 6-8, date from 1761, during Haydn’s first months in his new position. The symphony as a form was taking shape in these years (in fact, it was largely Haydn who would define that form), and these three early works show certain elements that did not survive in the symphony of the classical period—primarily the extended use of solo players who stand in contrast to the larger orchestra. Many have been quick to identify this as the influence of the baroque concerto grosso, although there is disagreement as to how well Haydn knew that form. In any case, the Symphony No. 6 has important solo parts for winds, violin, cello and doublebass.

Haydn may have felt an aversion to descriptive music, but the Adagio that opens the first movement of the Symphony No. 6 is clearly a depiction of the rising sun. Across that six-measure introduction, the music begins with softly pulsing violins, climbs upward and gathers strength, and lands on a resplendent fortissimo chord. From out of this “sunrise,” the music leaps ahead smartly at the Allegro, which is in a tentative sonata form: Its second subject, built on nicely calculated echo effects, makes a fleeting appearance and then never returns.

The longest of the movements, the Adagio—scored only for strings—offers extended solos for violin, cello and doublebass. The movement is in ternary form: The opening Adagio leads to the long central Andante; Haydn rounds off matters with a modified reprise of the opening Adagio. The wind band returns for the sturdy Menuetto; H.C. Robbins Landon describes its trio section as sounding “far more baroque than anything in [Haydn’s earlier] symphonies.” It is largely a bassoon solo over bass-line accompaniment. The Finale showcases the orchestra and its various principal players: Solo flute leads the way, and in the course of the movement comes an extended passage of concertante writing for solo violin, as well as solos for various other instruments.

Hearing this music without knowing that it is nicknamed Le Matin, would we guess that it was inspired by the morning? Almost certainly not. What we do recognize in this impressive symphony is the high quality of the orchestra Haydn had created for Prince Paul Anton and the crisp writing for its solo players.

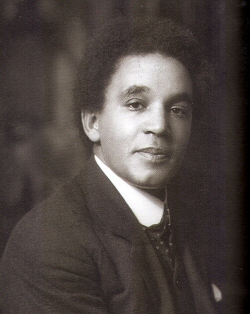

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

Born 1875, London

Died 1912, Croydon

Violin Concerto in G Minor, op.80

Born in London, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was the son of an Englishwoman and a doctor from Sierra Leone. His father, a descendant of slaves from North America, returned to Africa before his son was born, and his mother named the boy after the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, reversing the poet’s final two names in the process.

The boy was raised by his mother and her family, who were quite musical: They taught Samuel to play the violin and encouraged him to make a career in music. At age 15 he entered the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Charles Villiers Stanford. After graduation, he supported himself by composing, conducting, and teaching. He very early attracted the support of Edward Elgar, who recommended that the Three Choirs Festival commission a piece from him; this would be his Ballade in A Minor for orchestra, which helped establish his reputation.

Coleridge-Taylor was very interested in his heritage as the descendant of African-American slaves, and he dedicated himself to improving the condition of people of African descent everywhere. He made three extended tours of the United States, where he became acquainted with African-American and American Indian music, and he would eventually incorporate some of this into his music.

The Violin Concerto in G Minor was the final major work of Coleridge-Taylor’s all-too-brief career.

(He died of pneumonia at age 37). It was commissioned by the violinist Maud Powell, who had been an early champion of his music. The concerto went through two quite different versions. The first was based on what Coleridge-Taylor called “Negro melodies,” but he was so dissatisfied with that version that he burned it and wrote an entirely new concerto, which is the version performed today.

The Concerto in G Minor emphasizes both the lyric and virtuosic sides of the violin. The Allegro maestoso bursts to life with a grand fanfare for full orchestra. This figure, full of triplet rhythms, will return in various forms throughout the piece, and it is a mark of the composer’s sophistication that this fanfare contains the dancing, dotted rhythm that will form the movement’s second subject. The soloist enters on the fanfare theme, and soon the music leaps ahead on a Vivace based on the dotted figure. Near the end, Coleridge-Taylor gives the soloist a cadenza that is accompanied throughout by a quiet timpani roll, and the movement concludes with a powerful passage marked Molto maestoso (“very majestic”) as the violin sails high over powerful chords from the orchestra.

The Andante semplice takes us into a different world entirely. The orchestral strings, now muted, lay out the delicate principal theme, and soon the soloist takes this up and elaborates it. The orchestra leads the way into the central episode, marked Andantino, before the return of the opening material and a conclusion on the violin’s shimmering D, high above the orchestra’s final chords.

The concluding Allegro molto gets off to a fierce start with great orchestral salvos based on a dotted 3/8 figure. The soloist quickly picks these up and transforms them into a dancing finale in a generalized rondo form. There is flowing secondary material along the way, and as we approach the end, Coleridge-Taylor brings back the grand fanfare that opened the first movement.

Maud Powell gave the U.S. premiere performance on June 4, 1912, at the Norfolk Music Festival. The first public performance in England would place in London four months later, but by that time Coleridge-Taylor had passed away.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

Born 1862, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Died 1918, Paris

La mer

In the summer of 1903, the 41-year-old Debussy took a cottage in the French wine country, where he set to work on a new orchestral piece inspired by his feelings about the sea. To André Messager he wrote, “I expect you will say that the hills of Burgundy aren’t washed by the sea and that what I’m doing is like painting a landscape in a studio, but my memories are endless and are in my opinion worth more than the real thing which tends to pull down one’s ideas too much.”

That last phrase is a key to this music. While each of its three movements has a descriptive heading, La mer is not an attempt to describe the ocean in sound. Had Richard Strauss written it, he would have made us hear the thump of waves along the shoreline, the cries of wheeling sea-birds, the hiss of foam across the sand. Debussy’s aims were far different. He was interested not in musical scene-painting but in writing music that makes us feel the presence of the ocean; what mattered for Debussy was not the thing itself but his idea of that thing. At the premiere in 1905, the critic Pierre Lalo complained: “I neither hear, nor see, nor feel the sea.” But La Mer sets out not to make us see whitecaps but to awaken in us our own sense of the sea’s elemental power and beauty.

Debussy subtitled La mer “Three Symphonic Sketches,” and it consists of two moderately paced movements surrounding a scherzo. But these movements are not in the forms of German symphonic music, nor does Debussy write melodic themes capable of symphonic development. Rather, he creates what seem fragments of musical materials—hints of themes, rhythmic shapes, flashes of color—that will reappear throughout, like kaleidoscopic bits in an evolving mosaic of color and rhythm.

From Dawn til Noon on the Sea begins with a quiet murmur, a quiet that is nevertheless full of elemental strength. Out of this darkness, glints of color and motion emerge, and solo trumpet and English horn share a fragmentary tune that will return, both thematically and rhythmically, here and in the final movement. The movement builds to an unexpectedly powerful climax and a solitary brass chord winds the music into silence. Play of the Waves opens with shimmering swirls of color, and this movement is brilliant, dancing and surging throughout. It has a sense of fun and play, as a scherzo should. One moment it can be sparkling and light, the next it will surge up darkly. The movement draws to a delicate close in which a few solo instruments seem to evaporate into the shining mist.

The mood changes sharply at the beginning of the final movement. Debussy specifies that he wants Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea to sound “animated and tumultuous.” The ominous growl of lower strings prefaces a restatement of the trumpet tune from the very beginning, and soon the horn chorale returns as well. A gentle chorale for woodwinds sings wistfully at first, but the music builds to a huge explosion. Moments later, the pattern repeats, with the music again becoming calm and then hurtling to a tremendous finish.

—Program Notes by Eric Bromberger