Program Notes | Bartók Meets Beethoven

Sunday, March 26, 2023 / 4:00 pm

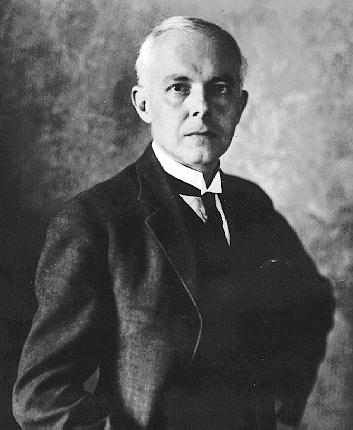

BELÁ BARTÓK

Born 1881, Hungary

Died 1945, New York City

Concerto for Orchestra in F Minor

Bartók and his wife fled to the United States in October 1940 to escape World War II and the Nazi domination of Hungary, but their hopes for a new life in America were quickly dashed. Wartime America had little interest in Bartók or his music, the couple soon found themselves living in near-poverty, and then Bartók’s health failed. He was hospitalized and fell into a deep depression, convinced that he would neither recover nor compose again.

Fritz Reiner and Joseph Szigeti convinced Serge Koussevitzky to ask Bartók for a new work, and the conductor visited him in the hospital to tell him that the Koussevitzky Foundation had commissioned an orchestral work for which it would pay $1,000. Bartók refused, believing he could not complete such a work, but Koussevitzky gave him $500 and insisted that the money was his whether he finished it or not. The visit had a transforming effect: Soon Bartók was well enough to travel to upstate New York, where he began composing. He completed the Concerto for Orchestra score eight weeks later.

The concerto premiered in December 1944 in Boston. It was an instant success, and Bartók reported that Koussevitzky called it “the best orchestra piece of the last 25 years.” Bartók prepared a detailed program note:

“The title of this symphony-like orchestral work is explained by its tendency to treat the single orchestral instruments in a concertant or soloistic manner. The ‘virtuoso’ treatment appears, for instance, in the fugato section of the development of the first movement (brass instruments), or in the perpetuum-mobile-like passage of the principal theme of the last movement (strings), and especially in the second movement, in which pairs of instruments consecutively appear with brilliant passages….The general mood of the work represents, apart from the jesting second movement, a gradual transition from the sternness of the first movement and the lugubrious death-song of the third, to the life-assertion of the last one.”

In the first movement, the music comes to life with a brooding introduction, and flutes and trumpets hint at theme-shapes that will return later. The movement takes wing at the Allegro vivace with a leaping subject for both violin sections, and further themes quickly follow. The movement drives to a resplendent close, stamped out by the brass.

In Giuoco delle Coppie (Game of Couples), Bartók varies the sound by having each “couple” play in different intervals: The bassoons are a sixth apart, the oboes a third, the clarinets a seventh, the flutes a fifth, and finally the trumpets a second apart. At the center of the Concerto lies the dark third movement, Elegia, based in part on material in the introduction to the first movement. This is one of the finest examples of Bartok’s “night-music,” with a keening oboe accompanied by spooky swirls of sound. In Intermezzo Interrotto (Interrupted Intermezzo), a sense of humor emerges with a woodwind tune whose shape and asymmetric meters suggest an Eastern European origin, continuing with a glowing viola melody derived from a Zsigmond Vincze operetta tune with the words “You are lovely, you are beautiful, Hungary.” Then Bartók quotes the ostinato theme from Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony (a theme he objected to, as it was associated with the Nazi invaders) and makes the orchestra “laugh” at it, treating it to a series of sneering variations and lampoons with rude smears of sound. The movement ends with a return to the Hungarian tune, now sung hauntingly by muted violins.

The Finale begins with a fanfare for horns, and then the strings take off and fly: This is the perpetual motion Bartók mentioned in his note for the premiere. This movement is of a type Bartók had developed over the previous decade, the dance-finale, music of celebration driven by a wild energy. Yet it is a most disciplined energy, as much of the development is built on a series of fugues. The piece ends with one of the most dazzling conclusions to any piece of piece of music: The entire orchestra rips straight upward in a dizzying three-octave rush of sound.

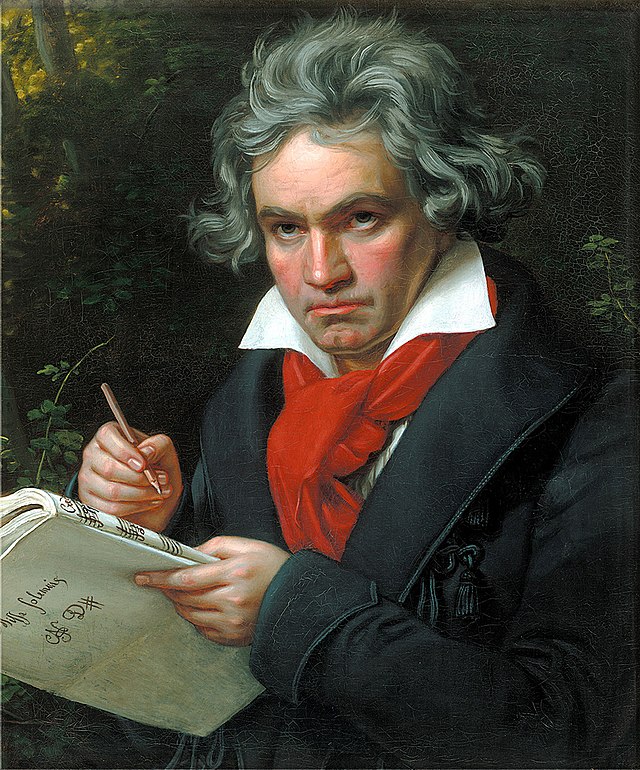

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born 1770, Bonn

Died 1827, Vienna

Symphony No. 7 in A Major, op.92

By the time Beethoven turned 40, his hearing had deteriorated to the point where he was virtually deaf. But he was still riding that white-hot explosion of creativity that has become known, for better or worse, as his “Heroic Style.” Over the decade-long span of that style (1803 to 1813), Beethoven essentially re-imagined music and its possibilities. The works that crystalized the Heroic Style—the Eroica and the Fifth Symphony—unleashed a level of violence and darkness previously unknown in music (forces that Beethoven’s biographer, Maynard Solomon, described as “hostile energy”) and then triumphed over them. In these symphonies, music became not a matter of polite discourse but of conflict, struggle and resolution.

A year later, the composer began a new symphony that would differ sharply from those two famous predecessors. Gone is the sense of cataclysmic struggle and hard-won victory that had driven those earlier symphonies. There are no battles fought and won in the Seventh Symphony; instead, this music is infused from its first instant with a mood of pure celebration. Such a spirit has inevitably produced a number of interpretations as to what this symphony is “about”: Berlioz heard a peasants’ dance in it, Wagner called it “the apotheosis of the dance,” and more Solomon suggested that it is the musical representation of a festival, a brief moment of pure spiritual liberation.

But it may be safest to leave the issue of “meaning” aside and instead listen to the Seventh Symphony simply as music. There had never been music like this before, nor has there been since; it can be argued that it contains more energy than any other piece of music ever written. Much has been made (correctly) of Beethoven’s ability to transform small bits of theme into massive symphonic structures, but in the Seventh he begins not so much with theme as with rhythm: He builds the entire symphony from what are almost scraps of rhythm, tiny figures that seem unpromising, even uninteresting, in themselves. Gradually, he unleashes the energy locked up in these small figures and from them builds one of the mightiest symphonies ever written.

The first movement opens with a slow introduction that is so long it almost becomes a separate movement of its own. Tremendous chords punctuate the slow beginning, which gives way to a poised duet for oboes. The real effect of this long Poco sostenuto, however, is to coil the energy that will be unleashed in the rest of the movement. The second movement, in A minor, is one of Beethoven’s most famous (at the work’s premiere and at several subsequent performances, the audience demanded an encore of the movement), but the debate continues as to whether it really is slow. Beethoven could not decide whether to mark it Andante (a walking tempo) or Allegretto (a moderately fast pace). He finally decided on Allegretto, though the actual pulse is somewhere between those two.

The Scherzo explodes to life on a theme full of grace notes, powerful accents, flying staccatos and timpani explosions. This alternates with a trio section for winds reportedly based on an old pilgrims’ hymn. Beethoven offers a second repeat of the trio, then seems about to offer a third before five abrupt chords drive the movement to its close. These chords set the stage for the Allegro con brio, again built on the near-obsessive treatment of a short rhythmic pattern, in this case the movement’s opening four-note fanfare. The four-note pattern punctuates the entire movement. The conclusion is Bacchanalian in its wild power; no matter how many times one has heard it, the ending of the Seventh Symphony remains one of the most exciting moments in all of music.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger