Program Notes | O Roméo, Roméo!

Sunday, Feb 19, 2023 / 4:00 pm

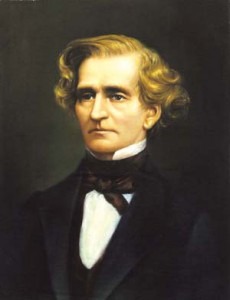

HECTOR BERLIOZ

Born 1803, La Côte-St-André

Died 1869, Paris

Roméo et Juliette: Symphonie dramatique, op.17

Roméo et Juliette, which Berlioz considered his finest work, was shaped by three quite different events. In 1827, he went to see productions in Paris of Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. The 24-year-old composer did not speak a word of English, but he fell in love with Shakespeare’s language and drama (and with Harriet Smithson, the actress who played Ophelia and Juliet in those productions; he would marry her nine years later). The second event was the failure of his opera Benvenuto Cellini in September 1838, an event that Berlioz described as leaving him feeling “stretched on the rack.” That failure blocked any further possibility of his producing an opera in Paris.

But three months later came an unexpected stroke of good fortune. Nicoló Paganini had commissioned a work for viola and orchestra from Berlioz, who responded by composing Harold in Italy. Paganini never played Harold, but as a gesture of gratitude he gave Berlioz 20,000 francs. That unexpected gift set Berlioz free; he paid off his debts and was suddenly free to write exactly what he wanted to. And his thoughts immediately turned to Romeo and Juliet. Berlioz and the poet Emile Deschamps prepared a libretto, though they based it not directly on Shakespeare’s play, but on impresario David Garrick’s version of the play, which made a number of changes. Premiered in Paris in November 1839, Roméo et Juliette was a tremendous success, one of the few moments of triumph that Berlioz enjoyed in Paris.

Roméo et Juliette is in a completely original form. Berlioz called it a Dramatic Symphony with Choruses, Vocal Solos, and Prologue in Choral Recitative, after the tragedy of Shakespeare. Maybe the best way to describe Roméo et Juliette is to explain what it is not. It is not an opera. It is not a setting of Shakespeare’s play or language. Nor is it a symphony in the sense that Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert understood the term. In Berlioz’s work, Romeo and Juliet do not actually appear, nor do Mercutio, Tybalt or the nurse. Instead, Berlioz uses a chorus and three vocal soloists to set the scene or respond to certain situations within the play, and he has the orchestra tell the story in some of the most beautiful music he ever wrote.

Berlioz divides the work into three parts that span 90 minutes. Part I bursts to life with a bristling orchestral fugato, full of trills and stinging attacks, that depicts the street warfare between the Montagues and the Capulets. Their fighting is interrupted by a magnificent entrance of brass instruments as the Prince enters and demands that the fighting stop. In the Prologue the chorus sets the scene: Two families are at war in Verona, and Romeo is distraught. In Strophes, the mezzo-soprano soloist sings (almost speaks) of the transforming power of love, and in the Recitatif the tenor soloist recalls Mercutio’s invocation of Queen Mab, the fairy of dreams and nocturnal adventures.

Part II brings three great orchestral movements: 40 minutes of instrumental music with only occasional commentary from the chorus. Romeo Alone finds him brooding and sad; the sound of distant revelries at the Capulets’ ball intrudes and soon takes over the movement, driving it to a powerful close. Love Scene is set on a “starlit night” in the Capulets’ garden. The guests departing the ball celebrate and call to each other, and then we move into the love music itself. At 18 minutes, this is the longest movement in Roméo et Juliette, and it is also the most heartfelt. Beginning softly with muted strings, it grows agitated and builds to a soaring climax. Arturo Toscanini, who made a memorable recording of Roméo et Juliette, reportedly called this movement “the most beautiful music in the world.” The Queen Mab Scherzo depicts the “fairy of dreams,” whom Mercutio had mentioned earlier. This is an extremely difficult movement for the orchestra. Berlioz marks it Prestissimo, sets it in 3/8, and mutes the strings, and on gossamer textures the music dances agilely along its furious tempo.

Part III opens with the Funeral Procession of Juliet (Berlioz assumes that we know the play and know that in the interim Tybalt has killed Mercutio, Romeo has killed Tybalt, and Friar Laurence has given Juliet the sleeping potion). Strings begin with a grieving fugue over which the women’s chorus sing “Jetez des fleurs” (“Cast the flowers”). Now comes the final orchestral movement, Romeo at the Tomb of the Capulets, which depicts Romeo’s anguish, Juliet’s awakening, their joy and despair, and their death. Berlioz marks the beginning Allegro agitato e disparato, con moto, and it gets off to a most violent start, but this quickly gives way to solemn chords and an Invocation, a brief lament from the winds. Juliet wakens to a great explosion of orchestral celebration, but the lovers’ happiness is short-lived–the music turns violent, falters, falls apart, and slips into silence as the lovers die.

Roméo et Juliette concludes with the Finale, and now Berlioz changes his idiom completely. He leaves behind purely orchestral movements and instead concludes with a scene that seems to have come straight out of an opera. Brass fanfares give way to crowds in the streets of Verona, confused and wondering what has happened. And now Friar Laurence—the one character from Shakespeare’s play to actually “appear” in the piece—explains that he had married Romeo and Juliet and given her the potion that simulated death. Romeo, mistakenly thinking her dead, took poison in the tomb, but Juliet suddenly woke and they shared a brief moment of happiness before Romeo died (remember that Berlioz was working from David Garrick’s version of the play, not from Shakespeare’s) and she stabbed herself with his dagger. Friar Laurence asks the two rival families to reconcile, but they refuse, and fighting erupts on music from the very beginning. Friar Laurence silences the families, invokes a curse if they refuse to reconcile, and asks God to teach them love and mercy. The families swear a joint oath of reconciliation and friendship, and Roméo et Juliette concludes in operatic splendor.

One of those who heard the 1839 premiere of Roméo et Juliette was an unknown 26-year-old composer named Richard Wagner. He was astonished by the originality of Berlioz’s conception and by the power of music by itself to advance action and create an emotional response; he called Roméo et Juliette “a revelation.” Twenty-five years later, Wagner sent Berlioz a copy of the score to his latest opera. His inscription is revealing:

from the composer of Tristan und Isolde

to

the composer of Roméo et Juliette

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger