Program Notes | Italian Nights

Sunday, March 17, 2024 / 4:00 pm

GIOACHINO ROSSINI

GIOACHINO ROSSINI

Born 1792, Pesaro, Italy

Died 1868, Paris

Overture to L’italiana in Algeri

L’italiana in Algeri (The Italian Girl in Algiers) was one of Rossini’s first great successes. He composed it in just 27 days in the spring of 1813, when he was only 21, and the opera was soon enjoying simultaneous runs in Venice, Verona, Brescia, Treviso, and other cities.

The opera combines the basic framework of an opera buffa with certain elements of the opera seria. It tells the story of the oafish Mustafa Bey of Algiers, who grows tired of his wife, Elvira, and insists on marrying the beautiful young Italian girl Isabella. The resourceful Isabella, however, has ideas of her own—she outwits Mustafa and escapes with her lover, Lindoro. Recognizing what has happened, Mustafa, now much wiser, returns to his wife. Listeners will recognize parallels with Mozart operas, particularly The Marriage of Figaro and The Abduction from the Seraglio, but Rossini treats these subjects with his own sparkling style and comic sense. The opera proved an instant success, and has held the stage ever since.

When pressed for time, Rossini often recycled earlier music, but he composed this entire opera afresh, including the overture, which has enjoyed a successful life in the concert hall. Quiet pizzicato strokes open the Andante introduction, and the music leaps ahead at the Allegro, where the woodwinds’ chattering theme is punctuated by great chords from the full orchestra. The orchestra is in sonata form, and its second subject is a long, arching idea for solo oboe. (Rossini would later use this theme as the basis for a replacement aria when the opera was produced several years later.) A brief development leads to a reprise of all the overture’s themes, which mark this music distinctly as the work of Rossini: long crescendos, a prominent part for piccolo, and sparkling energy. The overture is a perfect prelude to the complexities and fun to follow.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

Born 1809, Hamburg

Died 1847, Leipzig

Symphony No. 4 in A Major, op.90, “Italian”

Mendelssohn’s parents encouraged him to travel, and as a very young man he made a solo nine-month tour of Italy in 1830-31. It was a trip that brought pleasures beyond his dreams. He wrote: “Italy at last. And what I have all my life considered as the greatest possible felicity is now begun, and I am basking in it.”

While in Rome in October 1830, Mendelssohn began a symphony inspired by Italy and worked on it over the next several years, finishing it in early 1833. Although Mendelssohn loved Italy, he did not incorporate Italian themes into the symphony. This is the music of a very happy young German composer who celebrates Italy in his own musical language. Mendelssohn conducted the premiere in London on May 13, 1833 to great acclaim, but he was unhappy with the score and thoroughly revised it. He remained dissatisfied and planned to revise the final movement, but died before he could do so. The symphony was published in its second version four years after his death.

From its blazing beginning to its exciting close, the Italian Symphony is a marvel of color and energy, and it has one of the most effective openings in music. Over bubbling woodwinds, violins sing the surging main idea, and the high spirits of this opening establish a rocket-like momentum that will drive the entire movement. Two beautifully contrasted subordinate themes follow in turn: an amiable clarinet duet and a fugato, full of rhythmic snap that the second violins introduce at the start of the development. This movement overflows with energy; Mendelssohn reminds the orchestra to play staccato seven different times, and the music drives to a close as exciting as its opening.

Commentators have been unanimous in hearing a religious procession in the Andante con moto, but beyond that they differ sharply. One hears an old Czech pilgrim song, another a religious procession in Naples. In Rome, Mendelssohn saw the installation of Pope Gregory XVI; perhaps this movement was inspired by that ceremony. Outwardly, the third movement has the minuet-and-trio form of the classical symphony, but here the outer sections flow elegantly on long and seamless phrases, while the trio section features fairyland horn calls (prefiguring his incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

Mendelssohn’s one nod to native Italian music in this work comes in the final movement, which is a saltarello, an ancient Italian dance based on triplet rhythms and full of vigorous leaps. Mendelssohn uses three energetic themes in this movement (the sinuous third, which slithers between major and minor tonalities, is a tarantella), and the music dances happily to its fiery close, remaining in fierce a minor rather than returning to the A Major key of the first movement. So perfect a conclusion is this finale that it is difficult to imagine what changes Mendelssohn had planned during its revision and how it could possibly be improved.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

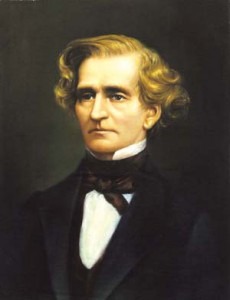

HECTOR BERLIOZ

HECTOR BERLIOZ

Born 1803, La Côte-St. André, Grenoble

Died 1869, Paris

Harold in Italy, Symphony with Viola obliggato, op.16

Early in 1834, Berlioz was approached by the great violinist Niccolò Paganini. Paganini had recently acquired a Stradivarius viola, and he wanted Berlioz to write a work for viola and orchestra. But Berlioz knew nothing about the viola and suggested that Paganini should write the piece. Paganini insisted, and Berlioz, who was desperate for success and income, accepted the commission. When he showed Paganini a draft of the first movement, Paganini objected to his entire conception: “That’s not it at all! I am silent too long in that; I must be playing the whole time.” So the two men went their separate ways: Paganini went to the Riviera where he tried to recover from the throat cancer that would eventually kill him, and Berlioz went on to complete the piece on his own.

If Paganini was one of the shaping influences on this music, another was Italy. In 1830, Berlioz had won the Prix de Rome, which involved an extended stay in that city. Berlioz fell in love with Italy, and his accounts of walking tours through the Italian countryside are some of the best parts of his Memoirs. A third influence was Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, which had been published in four cantos between 1812 and 1818. Childe Harold was the first appearance of the “Byronic hero”: the outsider; the rebel against conventional morality; the wanderer in search of meaning in a world of hypocrisy, cant, and materialism.

Berlioz described Harold in Italy as “a symphony in four parts with a principal viola” and went on to outline his method: “I conceived the idea of writing a series of scenes for the orchestra, in which the viola should find itself involved, like a person more or less in the action, always preserving his own individuality. By fitting the viola into my poetical memories of my peregrinations in the Abruzzi, I wanted to make the instrument into a sort of melancholy dreamer, in the style of Byron’s Childe Harold.”

The long first movement, Harold in the Mountains (scenes of sadness, of happiness, and of joy) takes the hero through the variety of moods suggested in its title. Berlioz transforms the principal theme into a slow fugue introduced by the double basses. In March of the Pilgrims, a slow introduction rings with the sound of distant bells. The music consists of two parts: the pilgrims’ hymn, sung by the first violins, and their prayers, announced by muttering woodwinds and second violins.

Dotted rhythms launch the third movement, Serenade of the Abruzzi mountaineer to his mistress. Soon the English horn gives us the sound of the mountaineer’s serenade, with the solo viola heard in counterpoint. The final movement is Berlioz’s portrait of the revelries of a gang of bandits in their mountain lair as they dance and carouse around a fire. Marked Allegro frenetico, this movement explodes to life and then plunges into some of Berlioz’s most orgiastic music. But then the viola vanishes and is silent for the rest of the movement, (except for a brief recall of the pilgrims’ march near the end), until the piece drives to a white-hot close.

Harold in Italy premiered in Paris in November 1834. Four years later, Berlioz, to his utter astonishment, received a gift of 20,000 francs from Paganini. The virtuoso never played Harold, but he admired the music and wanted to reward Berlioz. His opulent gift set the composer free: Berlioz was able to give up newspaper work and devote himself to composition. The funds made it possible for him to compose Romeo and Juliet, one of his greatest works.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger