Program Notes | Nochebuena Clásica!

Sunday, December 24, 2023 / 4:00 pm

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

Born 165, Fusignano, Italy

Died 1713, Rome

Weeping Willows

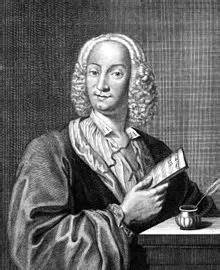

Mystery and controversy surround much of the life of Arcangelo Corelli. Born of a wealthy landowning family, he studied music at the cathedral of San Petronio in Bologna, a site with an illustrious pedigree of musicians and composers. Corelli is thought to have traveled extensively in Europe during his youth, but exactly where and when is not clear. He was teacher and mentor to an entire generation of violinists and composers, and the weekly musical soirées he led in the palace of his patron, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, became known throughout Europe. Preceding Vivaldi, Bach and Handel by only a generation, Corelli was in the forefront of developing the concerto as a genre.

Except for a few works, Corelli published all his compositions in six volumes of 12 works each. The first five sets were violin and trio sonatas; Opus 6 is a set of twelve concerti grossi, in which he set two violins and a viola (or cello) against a larger string ensemble.

The Concerto No. 8, also known as Christmas Concerto, is the best known of the set. Written for the church mass in celebration of the nativity, it is subtitled Fatto per la notte di Natale, but this has not restricted its performance to Christmas Eve. The Concerto has no true movements per se, but rather six short sections of music that flow together with brief transitional passages. The last, a Pastorale: Largo, is its most famous. But Corelli marked it “ad libitum” (at will), meaning that this lovely movement could be omitted; it is doubtful that anyone ever does. The Pastorale does not refer to a bucolic scene, but to the shepherds who gathered at the manger. The music becomes joyous, with long-held notes imitating the drone of bagpipes.

Program note by Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

ANTONIO VIVALDI

ANTONIO VIVALDI

Born 1678, Venice

Died 1741, Vienna

Guitar Concerto in D Major, RV 93

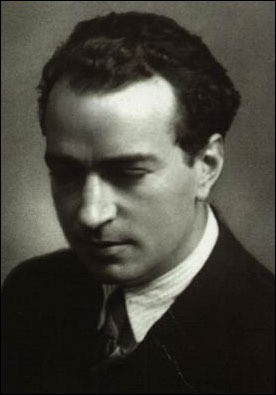

Vivaldi spent nearly 40 years (1704-1740) as music director of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for illegitimate, abandoned, and orphaned girls in Venice. In that era, perhaps more progressive than our own, the Ospedale believed that teaching these girls to play an instrument would give them a useful skill, rescue them from a life of poverty, and keep them from becoming lifelong burdens on the state. Vivaldi’s responsibilities were to teach violin and write music for the girls to play, and it was for them that he wrote most of his 450 concertos. The vast majority are for the composer’s own instrument, the violin, and he also wrote for other string instruments and winds. But apparently some of the girls played unusual instruments, and Vivaldi wrote for them as well; among these works is the Concerto in D Major.

This has become one of Vivaldi’s most popular concertos, and it exists in several forms. Although originally composed for lute and orchestra, it is probably best known in its present arrangement for guitar, but it has also been played on the mandolin and the violin. This popularity is no surprise at all. Its pleasing melodies, rhythmic vitality, and infectious spirits have made this concerto a favorite with both audiences and performers.

Perhaps because he was writing for an instrument that is not very powerful, Vivaldi scored this concerto for the unusual orchestra of only two violin parts and a basso continuo line. Much of this music’s effectiveness comes from the deft interplay of soloist and orchestra, for the ritornello themes are full of snap and energy, and they contrast nicely with the delicate but agile sound of the guitar. This concerto requires little description, and many listeners will discover they already know this pleasing music. It is in three movements in the expected fast-slow-fast sequence. Vivaldi launches the concerto with a firm Allegro giusto built on the orchestra’s rhythmic opening ritornello, and the soloist plays off the orchestra’s strong statements. The music feels constantly alive, from the snapped 32nd-notes of the ritornello through the busy runs that are exchanged by soloist and orchestra. An expressive Largo is followed by a concluding Allegro that dances (gallops?) happily along its 12/8 meter.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

JOAQUĺN RODRIGO

JOAQUĺN RODRIGO

Born 1901, Sagunto

Died 1999, Madrid

Concierto de Aranjuez

Since its premiere in Madrid on December 11, 1940, the Concierto de Aranjuez has remained Joaquin Rodrigo’s most popular composition. Its appealing tunes, virtuoso guitar part, bright colors, lively rhythms, and an imaginative fusion of guitar and orchestra have made it perhaps the most famous guitar concerto ever written. In addition, the music became a sort of rallying point in Spanish music: In the gloomy and demoralized period following the Civil War, this work showed Spanish composers how they might make use of their own musical identity.

Rodrigo liked to associate his compositions with specific locations in Spain. The Concierto de Aranjuez takes its title from the small town that was once a royal residence. Located about 30 miles south of Madrid, Aranjuez is still famous for its gardens. While the concerto contains no folk elements, Rodrigo has noted that in this music he was trying “to evoke a certain time in the life of Aranjuez —the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century at the court of Charles IV and Ferdinand VII. It was an epoch subtly characterized by ‘majas’ [the steretypical image of a traditional Spanish woman, often holding a folding fan] and bullfighters . . .”

At the very beginning of the Allegro con spirito, the guitar announces the rhythm that will underlie much of the movement, and quickly the orchestra enters with the first of the movement’s dramatic, almost declamatory, themes. Rodrigo takes special care to insure that the guitar is not buried by the orchestra: Soloist and orchestra take turns with the themes rather than competing with each other, and Rodrigo assigns much of the orchestra’s work to solo winds and solo cello.

As long as the two outer movements combined, the Adagio opens with bare chords from the guitar. Over this accompaniment, English horn sings the long and haunting melody that will dominate the entire movement. Soon the guitar takes this up, and the melody passes between soloist and orchestra, growing dramatic before the movement comes to a quiet close. The concluding Allegro gentile, which the composer has described as “a courtly dance,” is built on only one theme, announced at the very beginning by the guitar. This recurs continuously, varied on each repetition, until the very end, which is made particularly effective by its understatement.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born 1756, Salzburg

Died 1791, Vienna

Symphony No. 36 in C Major, K.425 “Linz”

When Mozart and his wife were en route from Salzburg to Vienna in 1783, they stopped in Linz as guests of Count Thun, the wealthy father of one of Mozart’s students. They did not know until they arrived that the Count had scheduled a concert on Mozart’s behalf, for only a few days later. The composer wrote to his father: “On Thursday, November 4, I am going to give a concert in the theater, and as I have not a single symphony by me, I am writing at breakneck speed a new one, which must be ready by then. I now end because I positively must get on with my work.”

Even Mozart, who could write at blinding speed, must have felt a little pressed this time, but he finished the symphony on November 3rd. Yet there is not the faintest trace of rush about this magnificent music, which is polished and complete in every way. The Symphony in C Major is the first symphony Mozart wrote after moving to Vienna, and some have heard the influence of Haydn in the slow introduction, the singing slow movement, and the sturdy minuet. But the “Linz” Symphony, as it has come to be known, is pure Mozart, particularly in its perfect sense of form and expressive chromatic writing. There is a special quality about this symphony, almost impossible to define: The music glows with health and energy, its sunny C-major energy propelled along at moments by dotted-rhythm fanfares.

The thunderous slow introduction (the first such intro in a Mozart symphony) instantly rivets attention, but serves little musical purpose beyond that: None of its themes reappears in the rest of the movement. The movement leaps ahead at the aptly named Allegro spiritoso, where the first violins’ opening theme has a rhythmic snap that will characterize the entire symphony; the second subject is one of those wonderful Mozart themes that changes key and character even as it proceeds.

The Andante is a long flow of easy melody, so graceful that it is easy to overlook that Mozart does something extremely unusual here: He uses trumpets and timpani in a slow movement, and their color gives this music rare expressive power. The minuet is forthright (and somewhat foursquare), while the trio section, with its ländler tune in the winds, beautifully overlaps phrases in its later strains.

The Presto finale, in sonata form rather than the expected rondo, zips along with such unremitting energy that it almost feels like a perpetual-motion movement. So dazzling is this energy that the subtlety of Mozart’s writing nearly gets lost in the rush: All three of this movement’s themes are related. Throughout, Mozart’s chromatic writing allows the music to slide effortlessly through many different moods until the symphony is rounded off with a coda that is shining, heroic—and quite brief.

—Program Note by Eric Bromberger