Program Notes | A Thousand Nights

Sunday, Sep 11, 2022 / 4:00 pm

LILI BOULANGER

Born 1893, Paris

Died 1918, Mézy-sur-Seine

D’un matin de printemps

The younger sister of the great teacher Nadia Boulanger, Lili Boulanger was a musician of extraordinary talent. A student of Fauré, Boulanger was the first woman to win the Prix de Rome, but that promise was cut short by perpetually poor health and by an early death: She was only 24 when she died. So short a life inevitably means that one’s output is small, and today she is remembered for her vocal settings and a small amount of instrumental music. As might be expected from the sister of Nadia Boulanger, her music is beautifully crafted. She has been described as an impressionist, but more striking are her instinctive sense of form and an expressive control of what is at times a surprisingly chromatic harmonic language.

In 1917, late in her brief life, Boulanger composed two mood pieces, each inspired by a different time of day: The subdued D’un soir triste (“Of a Sad Evening”) and the lively D’un matin de printemps (“Of a Spring Morning”). She composed the latter first as a duo for violin (or flute) and piano, then arranged the music for string trio, and finally arranged it for full orchestra. She was still working on the orchestral version when she died early in 1918, and it was left to her sister Nadia to supply a certain number of dynamic and phrase markings. The music has been widely performed and recorded in all three versions.

Marked Assez animé (“Very lively”), the opening section bursts to life on the work’s dancing, dotted main theme. Listeners may be struck by the sense of instrumental color here―in addition to its many wind solos, this section has solo passages for the concertmaster, principal second violin, principal viola and principal cello. D’un matin de printemps is in three-part form, and it slows slightly for its central episode. Though slower, the mood remains upbeat (the performance marking here is ardent, heureux: ” “ardent, happy”), and one senses the influence of Debussy in both expression and instrumentation. Solo oboe leads the way back to the opening material, but that return is not literal, and tempos and colors shift subtly before the music reaches its lively conclusion on a great, happy swoop of sound. We are left wondering what might have been.

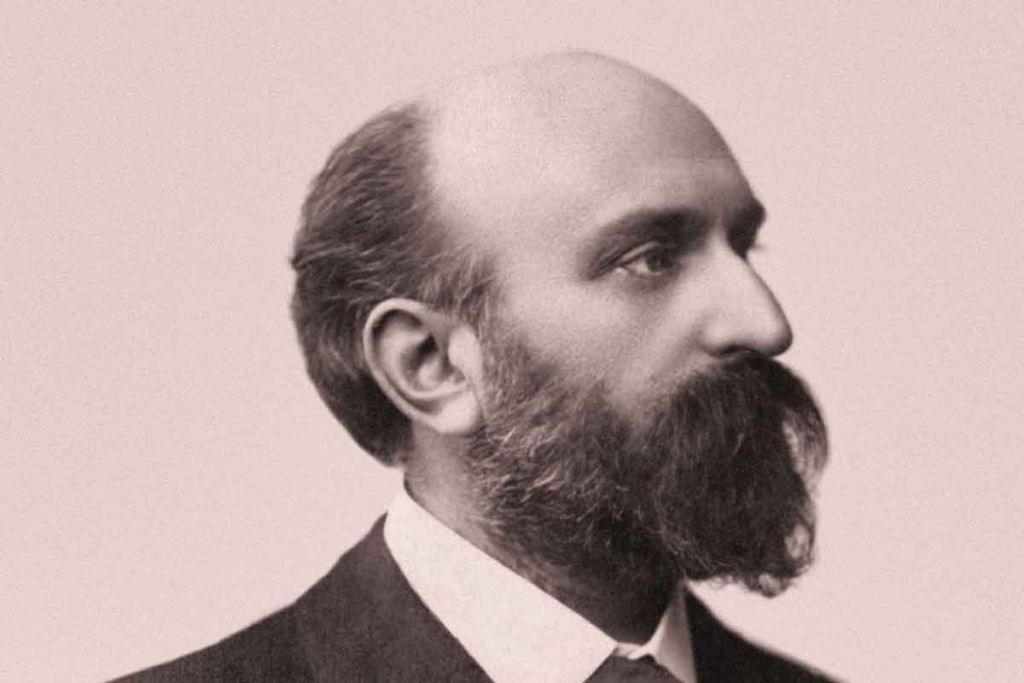

ERNEST CHAUSSON

ERNEST CHAUSSON

Born 1855, Paris

Died 1899, Limay, Yvelines

Poéme for Violin and Orchestra, op.25

Ernest Chausson grew up in an educated and refined family who believed that he should have a career in law. But the lure of music proved too strong, and after completing law school at age 24, he entered the Paris Conservatory. Perhaps because of this late start, it took Chausson some years to refine his art and develop a personal style, and it was not until his late 30s that he began to produce a series of carefully crafted works, particularly for voice. The promise demonstrated in this music was cut short, however, when Chausson was killed in a bicycle accident at age 44.

A cultivated man, Chausson was particularly attracted to the work of Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev. When he set out to write a piece for the great Belgian violinist Eugene Ysaÿe, Chausson turned to Turgenev’s work for inspiration, choosing a short story called (in its French translation) Le chant de l’amour triomphant. Chausson composed this music in the spring of 1896, although he finally chose the much simpler title Poème.

This 15-minute piece for violin and orchestra is neither a concerto nor a tone poem that sets out to tell Turgenev’s tale in music. Rather, it is a mood-piece—expressive, dark, almost voluptuous in its lush harmonies and melodies—meant to reflect the atmosphere of Turgenev’s tale. The musical form of the Poème is difficult to define: It is episodic, somewhat in the manner of a slow rondo. After the orchestra’s misty introduction, marked Lento e misterioso, the unaccompanied violin lays out the long and graceful main theme, which is repeated by the orchestra. The violin’s music grows more intense and florid, rushing ahead into the contrasting section, marked Animato, where it soars high above the murmuring orchestra. Chausson alternates these sections before the Poème moves to a quiet close on a return of the opening material. This ending drew particular praise from Debussy who, some years after Chausson’s death, wrote in a review: “Nothing touches more with dreamy sweetness than the end of this Poème, where the music, leaving aside all description and anecdote, becomes the very feeling which inspired its emotion.”

Although the Poème is not consciously a display piece, it is nevertheless quite difficult for the violinist, who must sustain a singing line (often high in the instrument’s register) and project the complex runs, trills and arabesques that give this music its distinctive character. Ysaÿe was very fond of the Poème and performed it several times (both privately and publicly) before the Paris premiere on April 4, 1897. Chausson had not had much success with critics or audiences, and the response to the Poème caught him by surprise: One of his friends told of seeing a look of astonishment on Chausson’s face as he stood backstage listening to the waves of applause that greeted the premiere: “I can’t get over it,” was all the amazed composer could say. A century later, the Poème remains Chausson’s most famous work, a favorite of audiences and violinists alike.

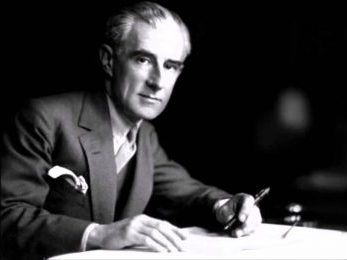

MAURICE RAVEL

MAURICE RAVEL

Born 1875, Ciboure, Basse-Pyrennes

Died 1937, Paris

Tzigane for Violin and Orchestra

In the summer of 1922, just as he began his orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Ravel visited England for several concerts of his music, and in London he heard a performance of his brand-new Sonata for Violin and Cello by Jelly d’Aranyi and Hans Kindler. d’Aranyi must have been a very impressive violinist, for every composer who heard her was swept away by her playing―and by her personality (Bartók was one of the many who fell in love with her). Ravel was so impressed that he stayed after the concert and talked her into playing gypsy tunes from her native Hungary―which went on until 5 AM.

Tzigane probably got its start that night. Inspired by both d’Aranyi’s playing and the fiery music, Ravel set out to write a virtuoso showpiece for the violin based on similar melodies (Tzigane means “gypsy”). Its composition was much delayed, however, and Ravel did not complete Tzigane for another two years. Trying to preserve a distinctly Hungarian flavor, he wrote the piece for violin with the accompaniment of a luthéal, a device that attaches to a piano and gives it a jangling sound typical of the Hungarian cimbalon. The first performance, by Jelly d’Aranyi with piano accompaniment, took place in London on April 26, 1924, and later that year Ravel prepared an orchestral accompaniment. In whatever form it is heard, Tzigane remains an audience favorite.

While Tzigane seems drenched in an authentic gypsy spirit, all of its themes are Ravel’s own. It is unusual for a French composer to be so drawn to this type of music. Usually, it was composers from central Europe―such as Liszt, Brahms, Joachim and Hubay–who felt its charm, but Ravel enters fully into the spirit and creates a virtuoso showpiece redolent of campfires and smoldering dance tunes. Tzigane opens with a long cadenza (nearly half the length of the entire piece) that keeps the violinist solely on the G-string across the span of the entire first page. Gradually, the accompaniment enters, and the piece takes off. Tzigane is quite episodic, and across its blazing second half Ravel demands such techniques from the violinist as artificial harmonics, left-hand pizzicatos, complex multiple-stops, and sustained octave passages. Over the final pages, the tempo gradually accelerates until Tzigane rushes to its scorching close, marked Presto.

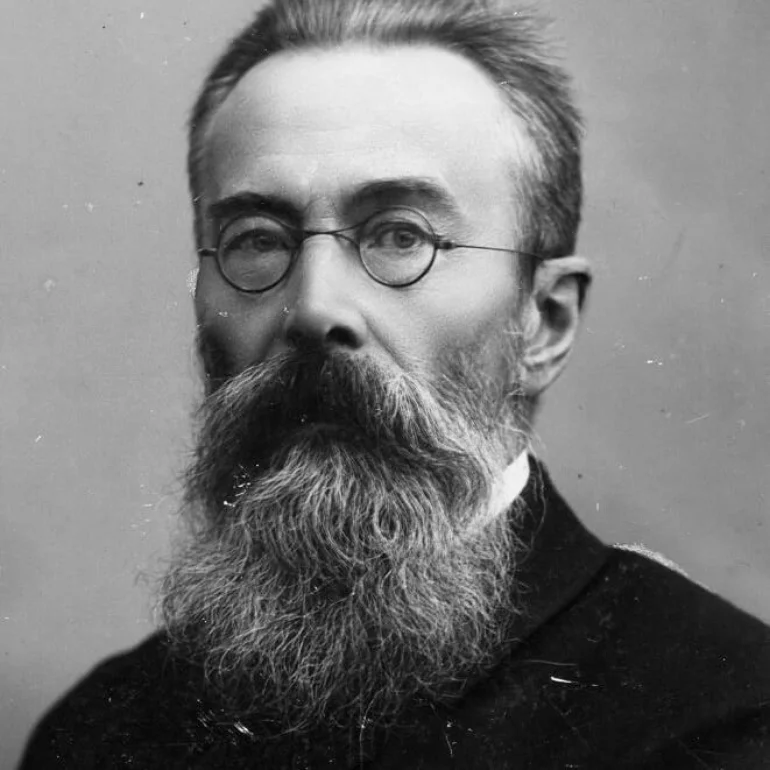

NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV

Born 1844, Tikhvin

Died 1908, Lyubensk

Scheherazade, op.35

In the summer of 1888, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, then 44 years old, went to his summer estate on the shores of Lake Cheryemenyetskoye and set to work on a new orchestral composition. He called it Scheherazade and added a subtitle, “Symphonic Suite on 1001 Nights,” that made clear its inspiration. Each movement had a title that suggested a definite program: The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship, The Story of the Kalender Prince, The Young Prince and the Young Princess, and the concluding Festival in Bagdad/The Sea, which ends with a shipwreck.

The composer included an introductory note in the score: “The Sultan Schahriar, persuaded of the falseness and faithfulness of all women, had sworn to put to death each of his wives after the first night. But the Sultana Scheherazade saved her life by arousing his interest in tales which she told him during a thousand and one nights. Driven by curiosity, the Sultan put off his wife’s execution from day to day and at last gave up his bloody plan altogether.” Scheherazade, composed within the month of July 1888, quickly became one of the most popular works in symphonic literature, played around the world, where audiences could revel in the stories with which the wily Scheherazade entranced her dangerous husband.

But does this music tell a story? Each of the movements has a descriptive title, and certain themes are obviously musical portraits: The menacing opening is clearly the ferocious Sultan, while the solo violin is the sly and sensual Sultana, spinning her tales. And along the way we hear the swaying sea, the sighs of the young lovers, the festival in Baghdad, and the crash of the ship against the rock.

Or do we? Despite what seems obvious musical portraiture, Rimsky-Korsakov discouraged any talk of this music’s telling a specific story and suggested that his intentions were much more general: “In composing Scheherazade, I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had traveled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions to the will and mood of each listener. All I had desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders . . .” The composer even went so far as to temporarily withdraw the descriptive titles of the four movements.

And so listeners are free to approach this music in any way they wish. They can experience it as the Sultana’s depiction of a thousand exotic tales and even imagine the specific events the music and movement titles seem to evoke. Or they can listen for Rimsky-Korsakov’s endless transformation of just a few themes, which return in an exotic array of new shapes and colors. Or they can listen for the opulence of the sound he is able to draw from the orchestra, for Scheherazade remains—more than a century after its creation—one of the most sumptuous scores ever composed. Perhaps some of the charm of this music is that it simply cannot be pinned down but remains as elusive, evocative and mysterious as the Sultana’s tales.

—Program Notes by Eric Bromberger